Growing up, Roberto S. Luciani had hints that his brain worked differently than most people’s. He’d hear people talk about how they pictured what a character from a book should look like, for instance. He couldn’t relate to what they meant.

But it wasn’t until he was a teenager that things finally clicked. His mother had just woken up and was telling him about a dream she had. “Movielike,” is how she described it.

“Up until then, I assumed that cartoon depictions of imagination were exaggerated,” Luciani says. “I asked her what she meant and quickly realized my visual imagery was not functioning like hers.”

He has a condition called aphantasia (AY-fan-TAY-zhee-uh). This is an inability to picture objects, people and scenes in one’s mind. When Luciani was growing up, the term didn’t even exist. Now he studies the condition as a cognitive scientist at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. He and other scientists are getting a clearer picture of how some brains work, including those with a blind mind’s eye.

In a recent study, Luciani and colleagues explored how our senses interact. In this case, they focused on hearing and seeing. In most people’s brains, these two senses work together. Sound information affects activity in brain areas that handle vision. But in people with aphantasia, this connection isn’t as strong. The team reported this November 4 in Current Biology.

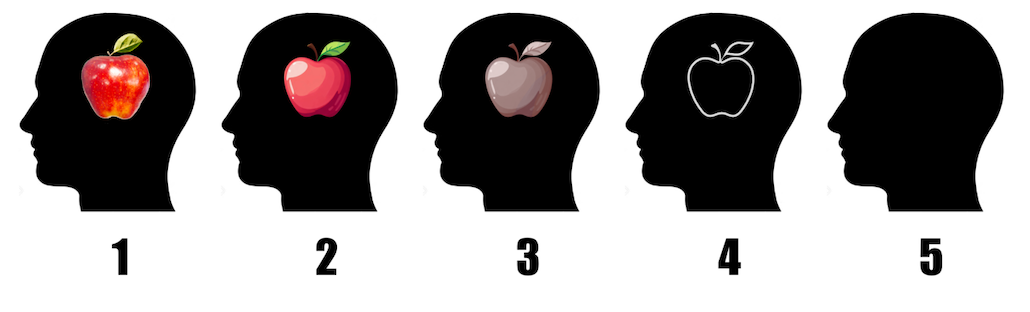

How our brains perceive the world can span a wide range of experiences. Some people generate very clear mental images of objects or ideas, as depicted on the left. Others, as shown on the right, may have little or no “mind’s eye.”Composition: Belbury, Images: Mrr cartman, Caduser2003, Bernt Fransson and IconArchive.com/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

How our brains perceive the world can span a wide range of experiences. Some people generate very clear mental images of objects or ideas, as depicted on the left. Others, as shown on the right, may have little or no “mind’s eye.”Composition: Belbury, Images: Mrr cartman, Caduser2003, Bernt Fransson and IconArchive.com/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)When the brain “sees” sound

The researchers recruited people to lay in a brain scanner, blindfolded. The volunteers listened to three sound scenes: A forest full of birds, a crowd of people and a street bustling with traffic.

In 10 people without aphantasia, these soundscapes kicked off activity in the brain’s visual system. It was as if the sounds led them to form a mental image. But in 23 people with aphantasia, these patterns were weaker.

The results show that senses can be linked within the brain to varying degrees, says Lars Muckli. He’s also a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Glasgow.

Learning how people with aphantasia experience the world offers a window into how the brain processes imagination, emotion and even memory.At one end of the range are people with synesthesia, he says. In this condition, sounds and sights are tightly mingled. For instance, someone with synesthesia might hear music as shapes or associate letter sounds with certain colors.

“In the midrange, you experience the mind’s eye,” Muckli says. Perhaps sounds trigger images in your mind, even though you know the pictures aren’t real.

“Then you have aphantasia,” Muckli says. “Sounds don’t trigger any visual experience, not even a faint one.”

The study results help explain how brains of people with and without aphantasia differ, Muckli says. They also give clues about how our brains work in general. “The senses of the brain are more interconnected than our textbooks tell us.”

The findings also highlight how people can make sense of the world in very different ways. Aphantasia “exists in a realm of invisible differences between people that make our lived experiences unique, without us realizing,” Luciani says. “I find it fascinating that there may be other differences lurking in the shadow of us assuming other people experience the world like us.”

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·