This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

In literary history, there are few constants like the writers’ feud. Aristophanes mocked Euripides; Dante put the contemporary poet Brunetto Latini in Hell; Norman Mailer famously head-butted Gore Vidal. But, as we’ve learned, it doesn’t have to be that way.

Our partnership began almost twenty-five years ago when we first became running partners. Our initial goal was to run a marathon. We were both working on our Ph.Ds at the time, and it seemed the perfect metaphor for writing a dissertation and entering a life in the humanities: long and strenuous, with uncertain outcomes. As we jogged by playgrounds, tennis courts, and the boat basin at 79th St., we talked constantly. We held each other accountable on grey days, and cheered each other on when we were tired. We grew stronger together.

We went from running partners to writing partners many years and children later. We had seen each other at our sweaty, exhausted worst, when our knees were aching and our calves were sore, so we were comfortable being vulnerable together. Like running, our writing partnership combined individual effort—we each wrote our on our own subject—and shared goals. We agreed to write every day, then text each other. “Done for today!” we would announce, and then shortly thereafter, the response would come, “Brava!” Accountability and reward, in one little ping.

That ping was powerful. We were at a stage of our lives, with young children and many commitments, where few paused to say, “Good job!” But through our partnership, we were guaranteed a bit of good feeling every day, which came from having our efforts, however small, acknowledged. Even a sentence or two, eked out in a rush, counted. And it’s by the accumulation of these tiny moments, word by word, that our books were ultimately born. We’d learned from running that a partnership is not a zero-sum game. As we wrote, we let go of the urge to compete—unlike those feuding authors from Aristophanes onward — so that we could both win.

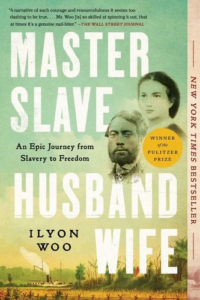

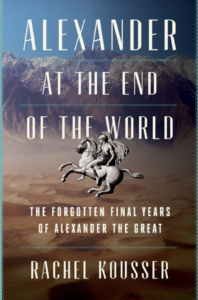

At the start, it was enough to write anything at all. Neither of us knew exactly what we were doing, or where we were headed. We were a Classical archaeologist, interested in writing for a broader audience, and a recovering academic, experimenting with fiction and screenwriting. We gave each other the courage to pursue projects that fascinated us. Over time, we both gravitated toward narrative non-fiction: For Rachel, the final years of Alexander the Great; for Ilyon, the true story of Ellen and William Crafts’ escape from slavery.

As we swapped book proposals and early drafts, we grew as writers and as editors. We learned to do what terrified us, whether that was writing without an outline, discarding an unworkable first draft, or approaching an agent. We benefitted from the fact that we were never afraid of the same things. Our different fears became especially apparent when Ilyon was interviewing with potential editors for her book, and in between interviews, pitched Rachel’s book to her agent and then her agent’s partner. (As it so happens, these agents also started out as good friends.) “Nooo!” wailed Rachel, when Ilyon announced triumphantly that the agent loved the idea and wanted to see the proposal at once. “I’m not ready!” But Rachel had learned to have faith in Ilyon’s judgment — and anyway, it was too late. Finally she relented, took a deep breath, and hit send.

Once we had agents and book contracts, our writing partnership changed and deepened. We now knew what our goals were, though the journey was unpredictable. On the surface of things, our subjects were as different as our personalities. These differences caused friction but also turned out to be our secret superpower. Lacking disciplinary blinders, we had no patience for each others’ particular obsessions.

“Too many pots!” said Ilyon of the multitude of ancient crockery in Rachel’s first chapter. “If you ever find yourself using any variations of the word archeology, know that you are going the wrong way.” We argued about descriptions of food, battles—“You’ve got to choose your battles,” insisted Ilyon, “Literally.”—and the role of minor characters. Our most heated disagreement was about William Wells Brown, a charismatic self-emancipated abolitionist, author, and friend of the Crafts, also Ilyon’s “archival crush.” He threatened to upstage the Crafts at various moments, most clearly on an expedition in the Lakes District that he took with a donkey (and without the Crafts). It was hilarious, but also a prime example of what we came to call a “stuffed sausage”: details that hid the story’s through-line with fatty padding. We discussed this expedition at length, and it remained in the manuscript for several drafts. But today the donkey passage is no more.

We also learned to support each other in our most difficult chapters, and personally difficult times. We struggled to do justice to our protagonists’ challenges—and to recognize the through-lines that carried them forward.Our styles of writing—our strengths and weaknesses—were complementary as well. As writers, we had profoundly different voices. Rachel had to unlearn her habit of academic writing, cutting every sentence that began, “Scholars have argued…” At the same time, she modeled for Ilyon a new attitude toward revising. Instead of clinging ferociously to what you’ve written, enter the space of literary creation as a place of trying on, as you might with a magical wardrobe of clothes: Keep what works, put back what does not, knowing that there’s an infinite budget, and no need to hoard.

As we worked together, we came to see unexpected parallels in the stories we were writing and in how we wanted to tell them. Our stories’ clearest parallels came from our protagonists’ journeys. Both had a goal, but as we ultimately realized, Alexander’s “end of the world” was not the end of his journey, just as crossing the Mason Dixon line was, for the Crafts, its own start.

We also learned to support each other in our most difficult chapters, and personally difficult times. We struggled to do justice to our protagonists’ challenges—and to recognize the through-lines that carried them forward. And as we wrote through these chapters and encouraged each other forth, we drew courage to find the through-lines in our own lives, together.

Almost a quarter century after we became running partners, we have yet to complete a 5K together, let alone a marathon. But we did finish our books, which were their own odysseys of sorts, ones where, as in the stories we told, our arrival at certain ends bloomed into new beginnings. We continue to disagree (productively, unlike the traditional feuding writers), but most of all, sustain each other in a collaboration that promises that no matter what other troubles there may be, there is this good we may depend on: that ping of being seen, from which both art and friendship grow. While the artistic process is represented as lonely and contentious, we are grateful to have found another way—a way that always has us looking forward to the next chapter.

______________________________________

Master Slave Husband Wife by Ilyon Woo is available now via 37 Ink.

Alexander at the End of the World by Rachel Kousser is available now via Mariner Books.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·