On the 4th of April 1908, The Times carried a short article on the “Release of Woman Suffragists.” Early the previous morning, forty women—who had been sentenced to 14 days imprisonment for “disorderly conduct outside the Houses of Parliament”—had been let out of Holloway Prison. Waiting for them at the gates was a large crowd of supporters, headed by Emmeline Pankhurst the founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union, who accompanied them on a victory parade across Central London. Led by a brass band, the women marched, singing activist songs and shouting campaign slogans, through the city streets.

This defiant procession ended, according to The Times, at the “Eustace Miles Restaurant at Charing Cross where the released suffragists were entertained at breakfast.” This was no ordinary restaurant. Spread over three floors and housing a gymnasium, advice bureau and lecture hall as well as several large dining rooms, it was the most popular vegetarian eatery in Edwardian London. It is significant that the first meal these prisoners chose to eat, voluntarily and as free women, was a meat-free one. As well as being somewhat surprising, it also sheds light on how political histories have been shaped by what we choose to consume and not consume.

Abstaining from meat was mobilized by these early feminist thinkers to challenge patriarchal assumptions, structures and systems.When we think of dining in early twentieth-century Britain stodgy steak stews, boiled mutton and mince pies probably come to mind before fruits and vegetables, but meatless restaurants were widely popular at the time. Following the founding of the first Vegetarian Society in Manchester in 1847 the movement grew in popularity and by 1900 there were over 20 vegetarian restaurants operating in London alone.

Open for nearly thirty years, serving over 1000 meals a day and enjoying the patronage of famous meat avoiders like George Bernard Shaw, the Eustace Miles was among the best-known restaurants in the city. This was due, at least in part, to its charismatic owner. Hailed in 1907 as the “Nut King, the Bean Emperor and the Milk Kahn,” the eponymous Eustace Hamilton Miles was an ex-Olympian fitness fanatic who built a health food empire that included a line of self-help books, a country retreat, a range of branded protein products and a popular monthly magazine.

Promoted as a “restaurant with ideals,” the Eustace Miles strived educate its customers in the benefits of the fleshless diet. In addition to serving lunch and dinner, it played host to evening lectures on food reform and satisfied diners could pick up a recipe book and recreate the restaurant’s menu at home. It was also a key site of progressive organizing in the city. The vegetarian diet had long served as a culinary expression of anarchistic, atheistic or otherwise radical political affiliations, and the Eustace Miles played host to discussions of socialism, spiritualism, temperance workers’ rights and importantly, female suffrage.

In 1912 Miles found himself in hot water when he was called up before the Magistrates Court to explain why he was “harboring dangerous criminals,” as several of the suffragettes who frequented his establishment were wanted by the authorities. He refused, rather gallantly, to reveal the identities of his customers and the restaurant continued to serve as a kind of social club for the Women’s Social and Political Union, who programmed a public lecture series in one of its upstairs rooms and set up campaign pitches on the pavement outside.

The Eustace Miles was not the only vegetarian establishment to fulfill such a purpose: the Gardenia in Covent Garden also played host to meetings and dinners, as did the Criterion on Piccadilly and the Teacup Inn off Kingsway. It is worth asking how meat free eateries came to be so essential to the suffrage campaign in Britain?

Part of the answer lies with the role that vegetarian restaurants played in the lives of women working in the city. Toward the end of the nineteenth century women entered the workforce as teachers, telegraphers, bookkeepers and typists in ever increasing numbers. This population—often young and usually unmarried—encountered an urban environment that offered new freedoms but also posed new challenges that had to be negotiated on a daily basis.

One of these everyday hurdles was the problem of where to eat lunch. As lone diners, unaccompanied by male companions, women were unable to safely access much of the city’s dining culture: they were discouraged by the rowdy chauvinism of chop houses and cautioned against the impropriety of eating on the street, some restaurants barred women from eating alone and women were excluded from gentleman’s clubs. These restrictions, coupled with the persistent threat of harassment, made the question of lunch essential to the socio-economic progress of women.

Into the gap stepped the vegetarian restaurant. In part because most did not serve alcohol and many discouraged smoking, they were seen as most respectable establishments, and their proprietors were keen to encourage to lone women diners. Several restaurants went as far as to offer special facilities to encourage female custom: the St. George on Martin’s Lane, the Wheatsheaf in Clerkenwell and the Elephant in Soho all boasted ladies’ tea rooms; the People’s Café Company in Farringdon advertised a dedicated ladies’ chess club; and the Pudding Bowl hosted an evening institute where women could learn practical skills, practice writing and improve numeracy. At the turn of the twentieth century, meat-free eateries were among the few public spaces where women could eat, socialize and learn without men.

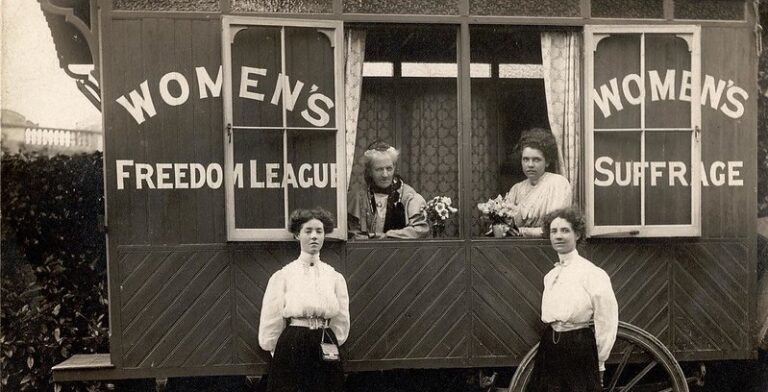

The connection between vegetarianism and suffrage goes deeper though. Suffragettes owned and operated several vegetarian restaurants, most notably the Minerva Café on High Holborn. Set up in June of 1916 by the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), a breakaway of the WSPU that advocated non-violent tactics, the business functioned as both the group’s headquarters and a means of generating income for the franchise campaign. The president of the WLF, Charlotte Despard, was a committed vegetarian and the Minerva Café functioned as a site of political organizing for not only suffragettes, but anti-war activists, anarchists and socialists also. When the Representation of the People Act was finally passed in 1918, the café served its patrons a celebratory menu of vegetable soup, lentil cutlets and rhubarb tart.

Meat-free eateries were essential spaces for socializing and campaigning, and this was because vegetarianism was a key moral touchstone for many radicals in this period. After Alexandrine Veigelé established the Women’s Vegetarian Union in 1895, the diet tendered itself as a cause for progressive women, alongside sexual reform, anti-vivisection, rational dress and higher education; and early feminist journals like Margaret Sibthorp’s Shafts—which described itself as a “magazine of progressive thought”—frequently published vegetarian recipes and articles voicing support for the cause.

In one of these, the writer Edith Ward argued for the adoption of a meat-free diet on the basis that “the case for the animal is the case for women.” According to Ward, the oppression of women and the exploitation of non-human animals resulted from the same system of power: to topple the gender hierarchy it would be necessary to also address species-based inequities. More than simply a dietary choice, abstaining from meat was mobilized by these early feminist thinkers to challenge patriarchal assumptions, structures and systems.

Identifying a link between the injustices faced by women and the plight of animals, suffragettes recast the dining table as a site of radical resistance and political disruption.One year after their victorious parade from Holloway Prison to the Eustace Miles Restaurant, suffragettes came up against a violent assertion of masculine authority in the form of force feeding. In 1909 an activist by the name of Marion Wallace Dunlop was convicted of defacing the House of Commons and sentenced to a month in prison. After the institution’s administration refused to class her as a political prisoner, Wallace Dunlop stopped eating and fast that lasted ninety-one hours, finishing only when she was released early as the prison management feared she might die otherwise.

Following this success, the hunger strike became a key strategy for the suffrage movement and a big problem for the government. Early release meant capitulating to the demands of a militant group but allowing female prisoners to slowly starve themselves to death was politically toxic. Force-feeding, a practice that had long been employed by asylum doctors, offered a solution. In cells across Britain women were held down, placed in restraints, their mouths prised open, and tubing force down their throats.

To draw attention to these brutalities, the WSPU circulated leaked letters written from inside prison that contained graphic descriptions of force-feeding and condemnations of the medical profession’s complicity in the torture of defenseless women. These shocking revelations generated considerable public concern and raised questions regarding the proper role of doctors in relation to the state, the rights of the incarcerated, and the scope of individual bodily autonomy.

Ultimately, the suffrage campaign turned the horror of force-feeding to their political advantage. Not only did it lend sympathy to the cause, the harrowing experience of being forced to eat, drink and digest against one’s will helped to forge solidarity among protesters. On release from prison, hunger strikers were awarded military-style medals to commemorate their courage and admirable commitment to the cause. Beginning with Marion Wallace Dunlop, these were distributed at celebratory breakfasts hosted by the Eustace Miles Restaurant. Dining on a menu of lentil soup, nut cutlets and chicory coffee, these courageous women united feminism with vegetarianism. Identifying a link between the injustices faced by women and the plight of animals, suffragettes recast the dining table as a site of radical resistance and political disruption.

__________________________________

From Rumbles: A Curious History of the Gut: The Secret Story of the Body’s Most Fascinating Organ by Elsa Richardson. Copyright © 2024. Available from Pegasus Books.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·