By Seeking Ithaca, Guest Writer

By Seeking Ithaca, Guest WriterFor the newcomers to this now nearly 4-year-old saga, here's a brief introduction. I, a new attending, and my family had recently been brought to a new city for a job. Having purchased a foreclosure for our family home, we discovered that the house was occupied by squatters. The occupants were practiced financial miscreants, having a long history of pecuniary malfeasance up to and including prior bankruptcy and mortgage defaults. We failed to amicably come to terms with the squatters, and we were forced to embark upon an ejection proceeding in the midst of the COVID-fueled judiciary backlog. Finding ourselves without a home, we were forced to rent a property and later to purchase a second home in order to house a growing family and enjoy some semblance of a normal life.

During that time, I employed an attorney to begin ejection proceedings, which proved a time- and money-intensive undertaking as legal proceedings are neither swift nor inexpensive. The squatters proceeded to launch a legal counteroffensive and slandered my title to the property. I realized that the slander of our title allowed us to invoke our title insurance policy—a piece of insurance which I’d thought a mere accoutrement to standard property sales, an anachronism from a time when ownership and clear title were commonly in question and record-keeping was still a matter of faded papers stuffed into a courthouse filing cabinet, edges curling and browning due to time and disuse.

Our title insurance placed us into the care of a punctilious and pernicious pedant for the law, a veritable legal polymath named John. He proceeded with a calculated attack on the squatter’s inappropriate possession of the house and mounted a spirited yet detailed riposte to their countersuits of slander of title and comically nonsensical allegations of “emotional and physical distress related to Seeking Ithaca’s slander of title.”

Cue the exaggerated eyeroll.

We’ve thus far been through an Orwellian deluge of judicial red tape and procedure-following and are in the process of deposing the squatters, eliciting repugnantly smug reponses by the squatters to our inquiries for information regarding their (lack of) payments on their mortgage and (lack of adequate) responses to their mortgage company for information as to why they declined to make their mortgage payments. Indeed, we find out that they’d not made a single mortgage payment in the two years since inhabiting the house.

Now that we have reconvened, I’m able to tell the tale to the last.

But first, if you'd like the full story, here's part 1 of this tale and part 2.

Overextended

Because of my Pollyannaish opinion on how long this dispossessory undertaking would last, my wife and I rented a small house for a year, moving our small family into a house about 1,000 square feet smaller than our home during residency. While Americans have a penchant for houses larger than necessary, 1,000 square feet smaller than what one has grown into feels like a shoebox by comparison. As our lease neared its close, my pregnant wife told me, in Seussian style, that she would not, could not agree to having another child in that small space.

This was in early 2021, and we’d already taken out a mortgage for the home which we currently owned that the squatters possessed (my wife got so jaded with the process that she sardonically began to call it “sponsoring a family”). Even with an attending income, swinging two house payments was going to be a stretch. Likewise, I was still building my practice in the town where we moved, and my salary floor would make an occupational medicine doc wince. However, we found a larger house on the outskirts of town that, though not updated since the Reagan administration, was still a big step up from the rental in which we were living. After making sure my disability policy could support two mortgages, we took the leap and bought the house: two mortgages, two insurance policies, and (soon) two children!

More information here:

Is Renting Better Than Buying? Why We’re Financially Independent and Renting

Can You Be Catfished by a Court Date?

Going to court can best be likened to playing in a casino: the house sets the rules. One month out from our court date, the clerk notified the parties that the judge had unilaterally pushed back the case another four months. If you’ll recall, the squatters, upon receipt of our initial ejection filing by our original attorney, filed that they not only wished to dispute the ejection but that they requested a full trial by jury. The clever tactic hidden in the request for a jury is that a jury trial takes longer—an order of magnitude longer, given that our municipality was dealing with a COVID-induced case backlog with the procedures for even safely assembling a jury still unclear for the court. This court date was ostensibly the date during which possession of the home would be determined.

Remember that this is a zero-sum game, where one party possesses the house while the other does not possess the house. Any and all postponements are effectively a win for the squatters.

In the background, John had been working on a second motion for summary judgment. A quick explanation: a motion for summary judgment is basically a legal request by one party to dismiss a case in favor of their party because the evidence is compelling and the law regarding the case is clear (the legal vernacular is that the case contains “no question of fact”). If granted, it dispenses with the case and gives a definitive legal ruling, just like one would get with a regular court date, but the judge rules on the case and not a jury.

We also had to decide whether to ask for monetary damages. It would be yet another battle over whether the financial loss caused by the squatters was worth pursuing and to what degree.

Consider this hypothetical. You, a primary care physician, have a patient who firmly denies that she has diabetes. Having watched one-too-many videos by a TikTok naturopath, the patient has decided that her real problem is intestinal parasites. Given only 10 minutes to complete the patient encounter by your private equity overlords, you must make a choice. You can choose to force the issue and explain that an A1c of 11 is not the result of nematodes and that glycated hemoglobin won’t actually respond to hyper-diluted ivermectin. Alternatively, you can negotiate by starting her on insulin in return for testing a stool sample for ova and parasites. Last, you can order the O&P and then fight the good fight when she returns a week later (provided she hasn’t been admitted for complications of hyperglycemia) and then go home at a reasonable time to see your kid’s lacrosse game.

This is the same framework through which the topic of damages (demesne profits) was viewed. The court holds that a property’s owner shall determine its fair market value or rent, but the opposing party can object to that valuation.

If we were to claim fair market value, the squatters would undoubtedly argue on the premise that I was inflating the amount to claim more than reasonable damages. It may tie up the case for longer, even if I could prove my valuation correct. If I claimed below fair market value, they could try and argue the valuation, but the judge might take an unfavorable view of the squatters—given that we’d submitted a low valuation of damages owed to us because of our leniency—and decide to rule in our favor. Unfortunately, you cannot go back after a ruling and change your valuation, so we would be accepting a certain amount of monetary loss to which we could never again lay claim. We could set an absurdly low valuation with an appeal in the motion that we are willing to take a big monetary loss just to put the matter behind us. The squatters would appear positively villainous to be contesting such a low figure, and the judge may look favorably on us for being so accommodating.[AUTHOR'S NOTE: *Pro tip: People appreciate any simplification of their duties and their work performing them.]

At John’s suggestion, we chose Option 2 and decided that delaying more than the nearly two years we’d already endured was emotionally more costly than we were willing to bear.

Details, Details

The hearing of the motion for summary judgment was heard, and I received a transcript—34 pages of small print—of the goings on during the hearing.

Case law pertains more to details than to the spirit of the statute. To wit, the opposing counsel, realizing their argument couldn’t be made on provisions of financial propriety, hung their proverbial hat on the idea that the original foreclosure was invalid because the months-long procedure didn’t adhere to the contract by one day. In mortgages, there are notices sent to the purchaser should they not pay. Out of multiple notices sent to and received by the squatters, they claim that the one notice notifying them of the acceleration of their mortgage (the lender essentially saying that they didn’t make payments, so now the whole balance is due unless you contact us ASAP) was not sent.

Since this would be a convenient plea for any mortgagor fallen behind on their obligations, the law then stipulates that the date the letter was mailed from the lender constitutes the beginning of that “period to cure.” The mortgagor can, within that period of time (usually 30 days), have one more chance to file a request for an amendment of the mortgage, make a payment (generously, one single payment pauses the entire process in my state), or work with the lender in some way to make arrangements. During those 30 days, the squatters sent in two requests for an amendment to the loan, notably missing several key pieces of financial information requested by the lender: balance in retirement accounts, balance in bank accounts, monthly income from their jobs, etc.

[AUTHOR'S NOTE: Internal monologue: One wonders how the squatters knew to submit requests for a loan amendment if the notice of mortgage acceleration and its attendant remedies were allegedly never received . . . ]

Though no complete loan modification or payments were made in that 30-day period to cure, the squatters, having made their bed poorly, were not willing to sleep in it. The argument by their counsel then pivots to (wait for it) how one counts days on a calendar. Their attorney argued that the squatters had, lamentably, only 29 days to cure their default and stop the mortgage acceleration and eventual foreclosure. Thus, deprived of their contractual rights stipulated in the mortgage, the squatters should indeed have a clear title to the property—all that payment stuff and missing income information notwithstanding. Text from the hearing below, shortened for length.

“THE COURT: And you're saying everything else fails? If you get notice 29 days instead of 30, everything after that fails, including the foreclosure, the actual foreclosure itself?

COUNSEL: It's not if you get notice [at] 29 days; it's if, in the notice, they give you the time period they tell you you have to cure is less than 30 days.

THE COURT: So, your clients were ready, willing, and able to cure the next day?

COUNSEL: That's irrelevant.

THE COURT: Well, no, it . . . it may be irrelevant, but it's a question I'd like for you to answer.

COUNSEL: Well, I think at that time my clients may have had the ability to cure and they didn't at that time. And like in . . . these other cases that we've cited and they have cited, Jackson and Turner, where the Court went back and reversed the foreclosure, no party cured, no party offered to cure. So, whether or not they could cure or offered to cure is not relevant to whether or not the notice is a proper notice.”

At this point, the judge demanded his clerk get a calendar, so that the two attorneys could physically demonstrate how they argued their truth about how 30 days should be counted. It’s a funny thing, the truth.

More information here:

How to Buy a House the Right Way

Are Foreclosures a Good Investment?

Rumblings of Motion

Though our definitive court date with the jury wasn’t set for several months later, the motion for summary judgment prompted a bit of a reaction on the part of the squatters. They proposed a settlement, which included their keeping the house, payment of rents to us for the time we owned the house, the mortgage company refunding our purchase price, and no attorney’s fees. In the most professional way possible, we told the squatters what they could do with that offer.

During the months that had elapsed between the deposition discussed in part 2 and the contemporaneous present time was that my wife had given birth to our second child. So long had these proceedings lasted that, between the writing of the first and this paragraph, our second child was conceived and delivered. Yet again, our court's definitive trial date was pushed back ex mero motu (unilaterally by the court without prompting from either party) for another seven months—at this point, it was an almost tragicomical event.

But . . .

Ordered, Adjudged, and Decreed

One month later, our attorney sent us that most highly anticipated of emails: we’d WON the motion for summary judgment! Issuing a blistering condemnation of the squatter’s financial misdeeds, the attempts to obscure and impede judicial proceedings, and the flimsy defense of their actions, the judge ruled in our favor for both the possession of the property and demesne profits. All was not settled, though. The judgment had an automatic 30-day stay (the period of time during which we could not “execute” the judgment and take possession of the house), with the squatters having 42 days to appeal. John filed a motion to ask the court to vacate the stay, given that the squatters had been in the house for over two years and, instead, provide us a writ of possession now.

[AUTHOR'S NOTE: The writ of possession is the piece of paper you take to the sheriff’s office, and they go door-knocking but not in the evangelistic way.]

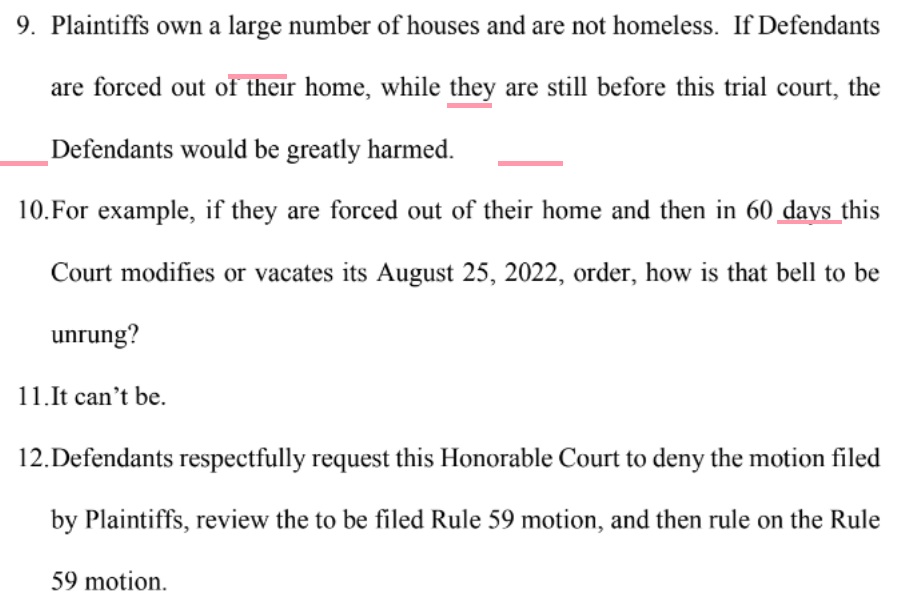

Characteristically, the Cheshire cat of an attorney whom the squatters hired filed this bit of comedy as a response.

In that lawyer’s opinion, a large number of houses for us is two houses—one of which, ironically, was a purchase made only because their client illegally (we can say that now that it’s been adjudicated) squatted in the first. Our modern era has a phrase for this: victim blaming.

Regarding the above, Rule 59 in my state is basically a way to ask the court to reconsider the ruling based on either new evidence or some misinterpretation of the law the losing party believes the court made. Though undoubtedly it would have taken up more of everyone’s time in legal proceedings, filing such a motion would have been expensive and unlikely to work, given how cut and dry the case was. Following their legal response, an email came from their attorney offering to move out voluntarily and not pursue Rule 59 if we agreed to drop the monetary damages, i.e., demesne profits.

After years of delay, stress on our family, paying two mortgages, and having already low-balled the “fair market rents” amount, my wife and I felt that this was flatly unscrupulous and told them not to let the metaphorical door hit them on the way out.

[AUTHOR'S NOTE: A deal/case isn’t closed until the cash/house is in hand.]

Unfulfilled Schadenfreude

One month later, before the date to file an appeal (Rule 59) had elapsed, we received an email that the squatters had moved out of the house. Jaded to the point of a green hue in my fingertips, I asked why they moved out before filing the appeal and before we could legally dispossess them of the house with the help of the county’s finest law enforcement officers.

Apparently, despite knowing that most of their neighbors and many people in our small town had gotten wind of the saga, having lied to their mortgage company, and having not paid their bills in years, the squatters felt that being asked to leave by someone with a starched shirt and badge was too damaging to their reputation. On the topic of character, I can’t guess what exactly this says of me, but the one bit of satisfaction to which I had been looking forward in this entire escapade was the visual ecstasy of watching a sheriff’s deputy physically remove this lowlife from my home with all the prejudice with which a surgeon removes a cancerous tumor.

If that bit of schadenfreude makes me a bad person, I can live with that.

Surveying the Damage

We first stepped inside our home the day after we received that email. No keys were delivered, so we contacted a locksmith to break us into our own home. Utilities off, cold and empty was the house. The interior was foreign to my wife and me—who, up to this point, had only seen our home in pictures on the internet from its sale to the erstwhile squatters. Walking the halls, we saw window AC units dotting the rear, trash in corners having been hastily thrown to the side when furniture was moved out. Walls damaged by hard use, though not ostensibly by malice; door handles loose; and smoke detectors missing from the ceilings were the house’s accoutrements. But despite the stained carpet, torn blinds, and bathrooms dingy from lack of cleaning and attention, it was finally in our possession.

My wife and I stood inside the unlit living room as the sun’s light was fading from the day, mottled by streaked windows, and cried. It was over.

More information here:

How to Move Up to the Next Level and Buy a Multi-Million Dollar Home

Almost There

We had a lot of work to do and not a lot of money with which to do it. I’d been working as much as possible, anticipating the day when we’d finally get into our home and knowing the labor that would be needed. We took out all the window treatments, removed the window units, and got utilities to the home. Finding the AC units so badly in need of repair that they were practically inoperable, we had them replaced, since it was cheaper than diagnosing and repairing them. We hired cleaners to scrub every inch of the home and hired a contractor for needed repairs and a few small updates.

That October, with the home still being cleaned and fixed, we handed out candy over Halloween to our new neighbors, telling them we were happy to soon be in the neighborhood. The basement needed updating, and the back porch and the landscaping needed replacing (shrubs had long since overtaken the windows and were working on the roofline). We methodically addressed each piece as we could with time and funds. In the meantime, after the squatter’s time to appeal had slowly ticked away, we found out that they had filed an appeal at the 11th hour.

Despite this, the day to move into our home had come. Under repair and renovation for six months, it was time to turn the key and walk as a family into our home. Still far from perfect, it was perfect to us, and we luxuriated in the knowledge that this was ostensibly ours. We sold our “temporary” house, benefitting from an increase in property values enough that we didn’t take a loss on the frictional costs of its rapid purchase and sale. We moved our things in and began living like a family.

The (State) Supreme Court Weighs In

Remarkably, the financial amount of the judgment against the squatters meant that their appeal was to be heard at the State Supreme Court. Smaller judgments would have landed us in appellate court, but this went all the way to the top. On the plus side, the Court was incredibly busy and might just decide to not hear the appeal, granting us a victory by default. On the other hand, if the court decided to hear their appeal, we could be years into just the appeal alone. On top of that, I’d spent nearly $100,000 repairing and renovating the property over six months, and I’d have sooner lit the house on fire than to lose it after living in and spending that much on it.

Fortunately, the first judge’s dispensation of the case had been fairly detailed, vehement even. Still, for the next seven months, my wife and I waited on pins and needles to discover whether we’d be dragged out of our home and be forced to start again. Thankfully, an early Christmas present arrived from the Supreme Court; it had considered the squatter’s appeal and discarded it out of hand.

Loose Ends

The last task was to collect on the monetary judgment rendered in the judge’s verdict, but who to ask? John, for all his work, was only employed by the title insurance company to defend our possession of the house. The insurance company wouldn’t pay him to collect these damages, and his hourly rate was such that I didn’t think I could afford him on my own. Having just finished a book on financial history in the United States, I remembered the appointment of Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. as head of the newly formed Securities and Exchange Commission by President Franklin Roosevelt. Asked why he would appoint a financial scoundrel like Kennedy, an inside trader and market manipulator grown rich off the spoils of his underhanded dealings, FDR replied with a glib, “It takes a crook to catch those crooks.”

Channeling the champion of the New Deal himself, I looked into attorneys whose practice it was to keep individuals who owed money from having to pay it. Calling one office, I told the attorney my situation, and he told me that he didn’t practice collections law; telling him my rationale, he laughed and agreed to take the case. Within three months, we had the money, minus his fees, from the squatters. Calculating the amount paid by the squatters, the sum came out to nearly what it would have been had they simply paid their mortgage when they owned the house. Inexplicable doesn’t begin to describe it.

In case anyone is interested, John’s attorney’s fees added up to over $200,000. This doesn’t count the costs of maintaining two homes, the cost of my original attorney, or the follicles that had turned grey during the proceedings. I heard that the squatters had moved to another home in the same town, though I can’t fathom how they could have been allowed to rent a home or purchase one. My wife has seen them a few times in the town we are in, and I have to remind her that she’s patently unsuited for prison and that horizontal stripes do nobody any favors.

In Summation

The operant question: was it worth it? While waiting on our home, we spent roughly $21,600 in rent; $8,000 in homeowner’s insurance (yes, we insured it while not living in it, ironically under a landlord’s rental insurance policy); $4,300 in attorney’s fees before we engaged John through the title insurance company; $100,000 in cleaning, repairs, and small updates; and $8,000 in moving costs between the three locations. That totals approximately $141,900.

When we bought the house, it was sold to us for around $115,000 less than the appraisal value at the time of the sale. By the time we moved in and fixed the broken and some of the outdated items of the house, it would appraise for roughly $265,000 more than we paid for it at the time and a net increase in value of about $123,100 ($265,000 of value above purchase price minus costs listed above). Financially, purchasing this foreclosure was a winning proposition, though we benefitted from a concomitant boom in the housing market that was likely responsible for around $75,000 of appreciation. Factoring that in, we assumed a net of $48,100.

Financially, the numbers pencil out post-hoc, but one can’t know that going into such a fraught endeavor. There are too many variables to reliably count on something like this working out out in the future: the disposition of the judge, the history with which you’re unable to account (the squatter’s financial history worked in our favor), the abilities and faculties of the attorney, the attention of the attorney to your case (largely dependent upon how much you pay them), the degree of time and expense which the opposing party are willing to spend to litigate, etc.

Emotionally, it was like the reverse of a roller coaster, mostly downhill with a wild swing upward at the end of the ride. My wife and I, despite being on the same team, argued bitterly over whether it was the right decision. Her desire for a nicer house was cooled precipitously by the repeated delays and obfuscation inherent in the legal system. Mine was driven by getting a “good deal” on a valuable asset with the makeup slowly wearing off and revealing the potential pig underneath.

Would I do it again? I have one clear answer. If I were to purchase a foreclosure again, it would only be as an investment property without my emotions tied to the outcome. I could dispense with the dealings as a cost of doing business and sleep soundly and without friction at home. Further, I would make sure the property was unoccupied or, if occupied, in a jurisdiction where the judiciary was politically property-rights favorable. Mine was in a jurisdiction where judges are fond of defendants in such proceedings and where every opportunity to give leeway is granted. Never again will I purchase a foreclosure for my personal home unless 1) I had sufficient comfort in my current surroundings that I could stay easily if it didn’t pan out, and 2) if the opportunity were so great at improving our current situation that I couldn't pass it up.

Given the degree to which our family has established itself here and the emotional attachment I now feel for this ostensible stacking of bricks and wood, I doubt I would ever leave my Ithaca.

Have you ever bought a foreclosed house? Have you dealt with squatters before? How long did it take to settle the outcome? What else did you learn?

The post The Truth About Buying a Foreclosed Home and 10 Other Ways to Provoke a Migraine, The Series Finale appeared first on The White Coat Investor - Investing & Personal Finance for Doctors.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·