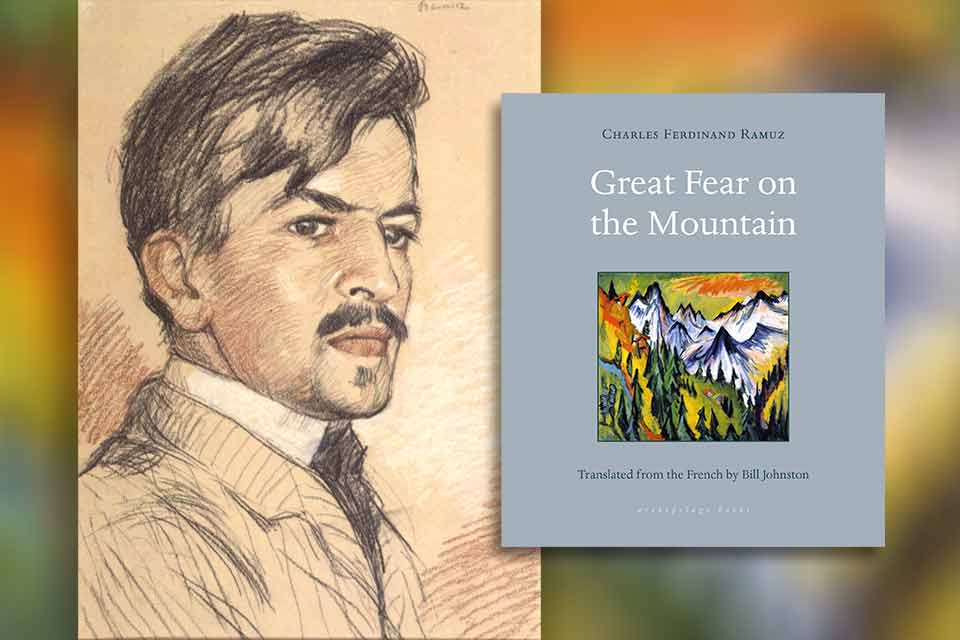

Caroline Cingria, C. F. Ramuz, pastel (1903) / Images courtesy of Noël Cordonier

Lumen Obscurum

Light and darkness are a major part of the global human experience; their contrast is a foundation of life and has always been the source of meditations and rituals. In Genesis, the creation of night and day separated order from chaos. Absolute light and darkness exist at the two extreme ends of a prism. St. Teresa of Ávila and St. John of the Cross defined both as the presence/absence of God. The brain responds to light and darkness. The Latin poet Virgil coined the term lumen obscurum (dark light), which the French playwright Pierre Corneille phrased as obscure clarté and the Polish poet Joanna Pollakówna as avare clarté.[1] The Polish poet Aleksander Wat and the German artist Anselm Kiefer titled one of their works Lumen obscurum. In his newly translated 1926 novel, Great Fear on the Mountain (Archipelago, 2024), Swiss-French writer Charles Ferdinand Ramuz (1878–1947) uses the term obscure lumière—rendered by translator Bill Johnston as “dim light.”

Merging light and darkness indicates a tension between seeing and not seeing, feeling and not feeling, knowing and not knowing. It indicates a pause during which fate hangs in the balance. It contains a vortex similar to the one created by forcing the opposite poles of a magnet together. It is a pause before total commotion. Throughout Great Fear on the Mountain, an alpine glacier provides these pauses to signal the characters’ increasing despondency. The final and most dramatic encounter occurs toward the end of the novel as life’s pause before death. Seven shepherds have been spending the summer on a high alpine pasture called Sasseneire, tending cattle and making cheese in hopes of earning extra income. But the cattle have taken ill, and the shepherds have scattered or are paralyzed by fear. The quarantine imposed by the village has separated two lovers: Véronique, drowned in her attempt to join her fiancé on the pasture, while Joseph was climbing down to see her. Having seen her death vigil, Joseph is now returning to the pasture. Overcome by grief, this valaisan Romeo stops in front of the glacier that dominates Sasseneire:

Perhaps it had been a dream before and this is now still a dream.

So he raised his eyes, turned to look upward over his shoulder, then brought his gaze to the front; he saw that the upper part of the glacier remained hidden. He saw that up above there was still that ceiling as if of yellow earth, like a large plain of clay seen from below, but after that the air was free, and at the same time filled with a dim light. (212)

Joseph next hears the glacier as a live monster that “burst out laughing” (213), swelling, cracking, and steaming, about to release a torrent of water, mud, and rocks into the valley below. Barthelemy, another shepherd, is walking toward Joseph; entranced, he is unable to notice “a sky of astonishing color, a color like the sun takes on when it’s viewed through smoked glass” (218).

Light, Sound, and Sight

Ramuz relies primarily on external perceptions of light, sight, and sound to describe the world. While darkness and light represent agony and ecstasy, silence and sound indicate togetherness and separation. These descriptions are not just for aesthetic or poetic purpose; they build suspense and echo the characters’ emotions. The result is a detective novel written cryptically, in Faulknerian style. The dominant emotion is a primal fear of nature’s vengeance against human encroachment, just as it happened twenty years before when shepherds and cattle first settled in Sasseneire for the summer. Scholars contend that the novel’s title was borrowed from Alphonse Aulard’s grand-peur that described the apocalyptic mood of the beginnings of the French Revolution in the summer of 1789. In Great Fear, the glacier tests the limits of human understanding and causes a loss of reality conducive to extracorporal and paranormal sensations, hallucinations, phantasms, and dreams. It becomes a purgatory to “vapors and legions of errant souls” experiencing a “hypnotic delirium, a kind of awake-dream.”[2]

Other settings that describe unfamiliar, disorienting light and sound effects include the mountain slopes’ dense forest, the absolute darkness of the night, the blinding light of the noon sun, and the silence of high altitudes’ “mineral world.” The magnificent sunrises on the jagged mountain summits are described in impressionistic, worshipping fervor, with dawn alighting on the landscape like a bird and the sky being so close that one could touch it. Sunsets, however, are daunting and taunting:

At the moment Joseph raised his head, the pink faded away on the glacier, which grew pale along its entire length, at the same time seeming to move forward and come to you.

It seemed to come toward you with a nasty color, an ugly pale color; and Joseph had no longer dared look, he’s quickened his pace even more, his head lowered; luckily the fine bright yellow light of the fire in the hearth soon appeared before him in the open door; and Joseph kept his eye fixed on the fire and did not look away again. (48)

Sounds are described with minute, realistic details, from homely village sounds to the alienating total silence of forest and pasture. Steps on the chalet roof, the crazy runs of mad cows, or the rumbling of the wind on the windows strike fear in the shepherds. The eternity of the mineral world is severely beautiful, forbidding, and frightful. The mountain is a blind and evil force. It smiles and threatens in turn, confining humans to the hospitability of the verdant valley.

Whether influenced by cinema’s visual possibilities, airplane feats, or his experience of the stage, Ramuz uses multiple perspectives to locate his characters.

If nature inspired in Ramuz his most lyrical descriptions and most beautiful images, these are made by a narrator-recitant whose disembodied observations disinvest the characters from their emotions, as seen in the central role of another visual effect. Whether influenced by cinema’s visual possibilities, airplane feats, or his experience of the stage, Ramuz uses multiple perspectives to locate his characters. At the beginning of the novel, the seven shepherds depart the village proudly with the cattle, but soon they too become small black points, barely visible, barely moving. Their ascent of the mountain slope is first seen from the walker’s standpoint, then from the standpoint of a villager looking up, then from a bird’s (camera, airplane) eye view. The narrator-witness-participant-stage manager’s multiple angles resemble Picasso’s three-dimensional portraits. This technique is an ode to the mountain; it measures its immensity and indicates existential separation. This happens to Joseph:

he was no longer even a dot amid the great areas of rock, through which he was threading his way; unseen, unheard, unseen by anyone, unheard by anyone; no longer even existing at moments, because he would disappear in a passageway. (83)

Language

Ramuz defined the artist’s mission as “quasi-religious.”[3] Language had to be sublime, perfect, starting with the craft of writing. Putting stories into words involved sheets of white paper, pen, ink, a desk, and the writer’s hand and body. This also meant creating a new language, an idea that Ramuz borrowed from Paul Cézanne. And in typical Ramuzian fashion, this meant many things. Already before World War I, Ramuz had eschewed the banality of “language-sign” in favor of a “language-gesture” that “reproduced the rhythm and ruptures of the spoken language and espoused sensations and emotions in a way that united land and language.” As formulated in the excellent postscript to Présence de la mort, his “very personal style, where Biblical reminiscences appear,” breaks with traditional syntax and strives to create an “oralized style” close to that of the characters.[4]

Ramuz affirmed that his true language was the langue d’oc of the Rhône region, the living language of the community he belonged to, and that le bon français was the culturally foreign language learned at school, a dead language.

Ramuz also refused a single linguistic mold, a stance familiar to the readers of Shakespeare who created a “high” poetic language while including “low” spoken English. In a letter to his editor Bernard Grasset, Ramuz affirmed that his true language was the langue d’oc of the Rhône region, the living language of the community he belonged to, and that le bon français was the culturally foreign language learned at school, a dead language:

We had two languages: one that passed for the “good” one, but that we used clumsily because it was not ours, and the other that was supposedly full of mistakes, but that we used well because it was ours. The emotion that I feel, I owe it to the things from here. . . . “If I wrote this spoken language, if I wrote our language . . .’ That is what I tried to do.[5]

And again in his correspondence:

The man who expresses himself really does not translate. He lets the motion happen inside of him until it is ready, letting it group words in his own way. The man who speaks does not have the time to translate. We had two languages.[6]

Ramuz’s linguistic choices meant that he used le bon français for description and local words and turns of phrase for dialogues and action. In Great Fear, the old-fashioned botille (water bottle) or the Germanic boube (youngster) are placed next to an austere, syntactically correct French. But then Ramuz inserts a third language. Having written 1,100 poems, he used poetic language for his descriptions of nature and called himself the writer of “poetic novels.”

How does one translate Ramuz? A prizewinning translator of Polish poetry into English, Bill Johnston has been translating francophone literature for a few years, such as Congolese novelists Alain Mabanckou and Koli Jean Bofane and French writer Jeanne Benameur. He translated Jean Giono’s Ennemonde in 2021, a novel that depicts nature as a powerful force and waxes poetic about the fauna and flora of Provence and Camargue.[7] In his readings of both Giono and Ramuz, Johnston was seduced by “the voice, the atmosphere, and the un-urban settings of their books,” for which he has given stellar translations. Such coup de coeur, such immediate and complete affinity with the novelist’s text, ensure a deep reading and understanding of the source text. Says Johnston, “For me, reading is above all an immersion in one particular text at a time; my immersions in Ramuz’s novels have each been magical, and through my translation of Great Fear I’d like above all to make that reading experience available to those who read English but not French.” Allying instinct to his training as a polyglot linguist, Johnston, who wisely chose to translate the 1926 version of the text, further explains his method. He retained what he calls Ramuz’s highly modernist “startling shifts of person and tense,” adding:

Ramuz counterbalances such dislocations of perspective with a lexical and syntactic palette that is quite austere—pared-down vocabulary, short simple sentences—a dimension of the source text that I also sought to reproduce in the English, and that somewhat mitigates the aforementioned “difficult” reading experience.[8]

Ramuz visiting with the Swiss editor Henry-Louis Mermod ca. 1940

Staging the Story

Ramuz reinvented the novel. After 1914, he abandoned the chronological and linear plots of expository novels. He multiplied the points of view to favor multiple explanations of facts and detached his characters from their emotions by inserting a detached narrator-recitant-witness-stage manager to orchestrate the story. Just as he reinvented the novel’s language, he renovated its style through “instability of the narrative instance, recourse to unhitched representations, willful confusion of the voices, multiplicity of points of view, rupture of the time frame.”[9] His abrupt changes of scenery and perspective and voices have been described as nouveau roman techniques; yet they are less arbitrary than it appears, for they are meant to “stage” each scene. Many of his indications of location, light, sound, and motion sound like stage and acting directions.

At the beginning of the novel, the “actors” are “taking their places.” Two men who are separated by their station in life are walking above the village. Clou is trying to convince the chairman to let him join the crew that will spend the summer on Sasseneire. He is an odd character, a restless wanderer who scares people because of his “strange encounters” on the mountain where he searches for gold.[10] The village chairman, who has been forced to arbitrate between the old and the young villagers, now has to choose the men who will lead the cattle to Sasseneire:

Through the color of the smoke, there could be seen the color of the slate roofs and the color of the wood; gray slates could be seen, along with walls made of weathered beams that were red, or brown, or black, on whitewashed bases. It could be seen that the roofs were keeping together, having gathered together, enjoying being together, pressing against one another in friendship; and Clou was saying that there was no hurry; behind their fences, the gardens could also be seen, starting to turn green and to be dotted with yellow, blue, and red. (23)

It was good behind the hedge, because they were sheltered from the eyes of others there. Opposite them were the mountains, which were turning pink. Conversations could be heard in the narrow streets, doors could be heard creaking on rusty hinges. The pig shed could be heard being bolted, emitting a long squeal like that of the animals it enclosed.

It was evening, the beginning of June, and at this point the men who would go up to the chalet ought to have been engaged already, yet no one had come forward, except Clou, as has been seen; so they were up there, the two of them, once again, by the hedge. It’d been a long while since either of them had spoken. Now the mountain in front of them was gray; even the highest tops had been stripped of their colors in the sky.

They were still saying nothing. She was waiting for him to speak first. In the end, she turned toward him; she was beginning to feel puzzled. She gazed at him a first time; she looked at him again as if asking: “What is it?” (23–24)

Are Clou and the chairman sheltering behind the hedge? Who are the nameless “she” and “he” mentioned at the end of this passage? Only later in the novel does the reader understand that the two characters behind the hedge are Victorine and Joseph. Upon a second reading, it is evident that Ramuz has fused two separate yet complementary scenes. Both sets of characters are separated from the village whose sounds and sights below them feel close-knit and familiar. Their immobility indicates a pause before making decisions that later will prove life-changing. The abundance of counterpoints strengthened by the multiple-perspective technique are established with authority by the narrator-stage manager. Thus an ordinary event is propelled into a timeless symbol, as in a Chagall painting.

An ordinary event is propelled into a timeless symbol, as in a Chagall painting.

Likewise, Ramuz stages the story of the curse. The curse is first told by the “old” villagers as a brief, elusive warning; then old Barthelemy, the sole survivor of the first tragedy and willing to dare the mountain again, tells the full story. He tells it in minute detail at night, in the pasture’s chalet, by the fireplace, when night’s darkness and eerie sounds are chilling the shepherds’ souls. In this modified setting, the en abîme narration of the mountain curse contrasts with the traditional veillées told in a safe environment to a tightly knit community. This scene is staged in cinematic fashion, with the fire’s dancing light and shadows and the precise notations of the body positions and movements of the listeners creating fear, and before the shepherds have succeeded in forming a cohesive community. Thus fear starts unraveling them one by one; in the end they all die or disappear. Ramuz uses Barthelemy to break the story’s timeline into separate units that will highlight the differences among the men.[11] Of the seven shepherds, two are very old, three very young, and two middle-aged. Poverty, after briefly uniting them, makes them vulnerable to the prospect of gain: cattle owners lack grazing land around the village, older men lack work opportunities, Clou is incapable of holding steady employment, and the young couple needs money to furnish the nest. Within this narrative structure, Ramuz succeeds in deepening the men’s characters considerably, albeit indirectly. This is supreme nonlinear technique.

Striding the Borderlands

Ramuz grew up in two cultures, Swiss and French. Born in a Protestant family in Lausanne with a faith strongly based in the Old Testament, deeply attached to the francophone and Catholic county of Valais, a friend of Jacques Maritain,[12] educated first in Lausanne then in Paris, he was attached to le terroir of his native country yet partook of the latest cosmopolitan intellectual and artistic currents of the early twentieth century. Like millions of other citizens living in borderland areas, he was enriched by multiple cultures and burdened with the resulting cognitive dissonance. He was a man of the borderlands, an “existential claustrophobe.”

Ramuz read the Bible assiduously, particularly the Old Testament and the Apocalypse, in the 1744 version sponsored by Jean-Frederic Osterwald, a Protestant theologian and pastor from Neufchâtel. The “concrete language” flavor of this version undoubtedly lingered in his works. Other readings ensured a well-rounded, multidisciplinary knowledge. He read an article on Freud about suicide and parricide; essays by French medical doctor and art historian Élie Faure, a student of Henri Bergson, and by the essayist, poet, and critic André Suarèz. He was part of the movement that valued the common people and practiced empathy for the poor. His operatic librettos and essay about Paul Cézanne show him as a friend of the arts. Having studied physicists Jean Perrin and Arthus Eddington and entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre,[13] he wrote about the Great Influenza epidemic of 1918 and called epizootics “a simple thing.” Theodule Ribot’s or Pierre Janet’s writings about the relationship between psychology and physiology may have left their mark on him as well.

Nature remained his focus, in particular the issue of global warming that had been studied since Joseph Fourier calculated the supposed earth temperature given its distance to the sun. Scientists’ concerns about a carbon dioxide “blanket” were heightened by the Industrial Revolution, and they blamed the rapid exploitation of natural resources for global warming.[14] Ramuz addressed this problem in his apocalyptic 1922 novel Présence de la mort (Presence of Death) and used it again in Great Fear three years later, only to resurrect it nine years later in Derborence. The continuity of this theme demonstrates his interest in environmental protection.

The social sciences’ influence on his work has been less studied. In the years preceding World War I, a true intellectual revolution was occurring with Fernand Braudel’s seminal work on the Mediterranean world, Lucien Febvre’s regionalist studies, and the Annales’ birthing of social history. The work of ethnologists about alpine legends captured Ramuz’s attention.[15] Ramuz used these influences to emphasize communal beliefs, collective behavior, collectivities’ struggles against the destructive forces of war, poverty, fear, and cosmic threats.[16] But he exposed the conflicts between science and legends, submission to fate and control of nature, and he explored the communal dissolutions caused by modernization.

Ramuz experienced the borderlands in a more playful way, by refusing to be imprisoned in a particular genre and using virtually every tool in the writer’s toolbox.

Ramuz experienced the borderlands in a more playful way, by refusing to be imprisoned in a particular genre and using virtually every tool in the writer’s toolbox. His novels bridge the three main literary genres by being poetic plays in prose. There is unity of place and time as in a Greek tragedy, along with disorientation and displacement. There is an unlikely Shakespearean love and a touch of Agatha Christie. Old and new realities and languages clash and coexist. Ramuz delighted in juggling places and times. He anchored several novels and short stories in the Catholic, francophone Swiss county of Valais, more precisely the village of Lens that he discovered in 1906, but he changed the village’s name. While the action of Great Fear was inspired mostly by popular legends, the county of Valais is home to a large number of important glaciers, and Ramuz must have known about the landslides that collapsed mountain pastures and often involved melting glaciers. In Great Fear, he mixed details from several stories, even bringing global warming as the cause of the Sasseneire glacier’s melting.[17] He dares his readers to solve the mystery surrounding the seven successive deaths and/or disappearances of the shepherds, and whether fate, divine punishment, climate change, the mountain’s meanness, or the devil caused the tragedies that befell Sasseneire.

Biography

Born in Lausanne to a Protestant family, Charles Ferdinand Ramuz was a Swiss poet, essayist, contributor to and editor of several French and Swiss literary journals; he was also a novelist who grew up during the European regionalist literary revival of the late nineteenth century. He spent his formative years in Lausanne and went to Paris under the pretext of pursuing a doctorate but got quickly caught up in the cosmopolitan artistic and intellectual life of the capital. He was nominated for the 1907 Goncourt Prize for his novel Les Circonstances de la vie, and the innovativeness and expressiveness of his style were appreciated by Paul Claudel, André Gide, and Louis-Ferdinand Céline. His prewar novels emulated Flaubert and Maupassant and focused on being true to “simple people” whose struggles are universal. Ramuz returned to Lausanne after the outbreak of World War I. He explored the artistic world with an essay on Paul Cezanne in 1914 and three librettos during World War I, one of which, L’Histoire du soldat (The soldier’s story), was written for Igor Stravinsky in 1918. The traumas of World War I accelerated his exploration of modernity and his disquietude before a changing world; he shared the new artistic currents that favored the fluidity of artistic forms, the shock value of representation, the stream-of-consciousness movement, and the deep psychological exploration of the soul. The tragedies of World War I heightened the entire interwar years’ fear of loss of European identity and place and made Ramuz a keen follower of current events.

The traumas of World War I accelerated his exploration of modernity and his disquietude before a changing world.

His works continued to receive accolades; his essay on the Vaudois painter Aimé Pache (1912) and Passage du poète (1923) both received the Rambert Prize. Great Fear was first published in 1925 in the Parisian journal La Revue Hebdomadaire in six installments, then in book form by Grasset in 1926, the first of Ramuz’s work by that publisher. In 1930 he won the Romand Prize, and in 1936 he received the Schiller Foundation Prize. Ramuz penned twenty-nine books during his career and has been called one the greatest French-Swiss authors of the twentieth century. His style influenced several writers, including Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Jean Giono. Yet his last years were saddened by his unsuccessful nomination for the Nobel Prize by the Swiss Writers’ Society in 1943 and 1944.

After his death in 1947, Ramuz still enjoyed a solid popularity. He can boast of more than twenty posthumous publications. The first translations of his novels by Milton Stansbury were published by Harcourt, Brace, and World in 1967. It would be fifty years before two other novels greeted English readers in Michele Bailat-Jones’s translation.[18] And now Bill Johnston has penned the first translation of Great Fear on the Mountain. A stamp with Ramuz’s image was issued in 1972, and a 200 Swiss franc note with his image was in circulation between 1997 and 2018. A Swiss federal train has been named after him, and plaques, buildings, and streets are named after him. Eighteen movies were made of his works between 1933 and 2006, notably one of Great Fear; two comic books and four theater adaptations were made. Gallimard published a two-volume set of his complete works, reproducing the original Grasset editions (La Pléiade collection, 2005), while Slatkine reprinted all twenty-nine volumes in the versions corrected by Ramuz and published by the Swiss editor Mermod in the early 1940s. Ebooks became available after his works fell into the public domain in 2017. To this day, however, there is not a solid biography of Ramuz in book form, although several scholars have focused on specific aspects of his work such as the coming of modernity, his biblical style, or his use of legends and his examination of fear.[19] His 1,100 poems remain the least well-known part of his work.[20] But the proverbial “writer’s purgatory” has finally ended, and the “regionalist” label’s shadow has stopped obscuring the innovativeness of Ramuz’s writings and their epic dimension.

University of Tennessee at Martin

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·