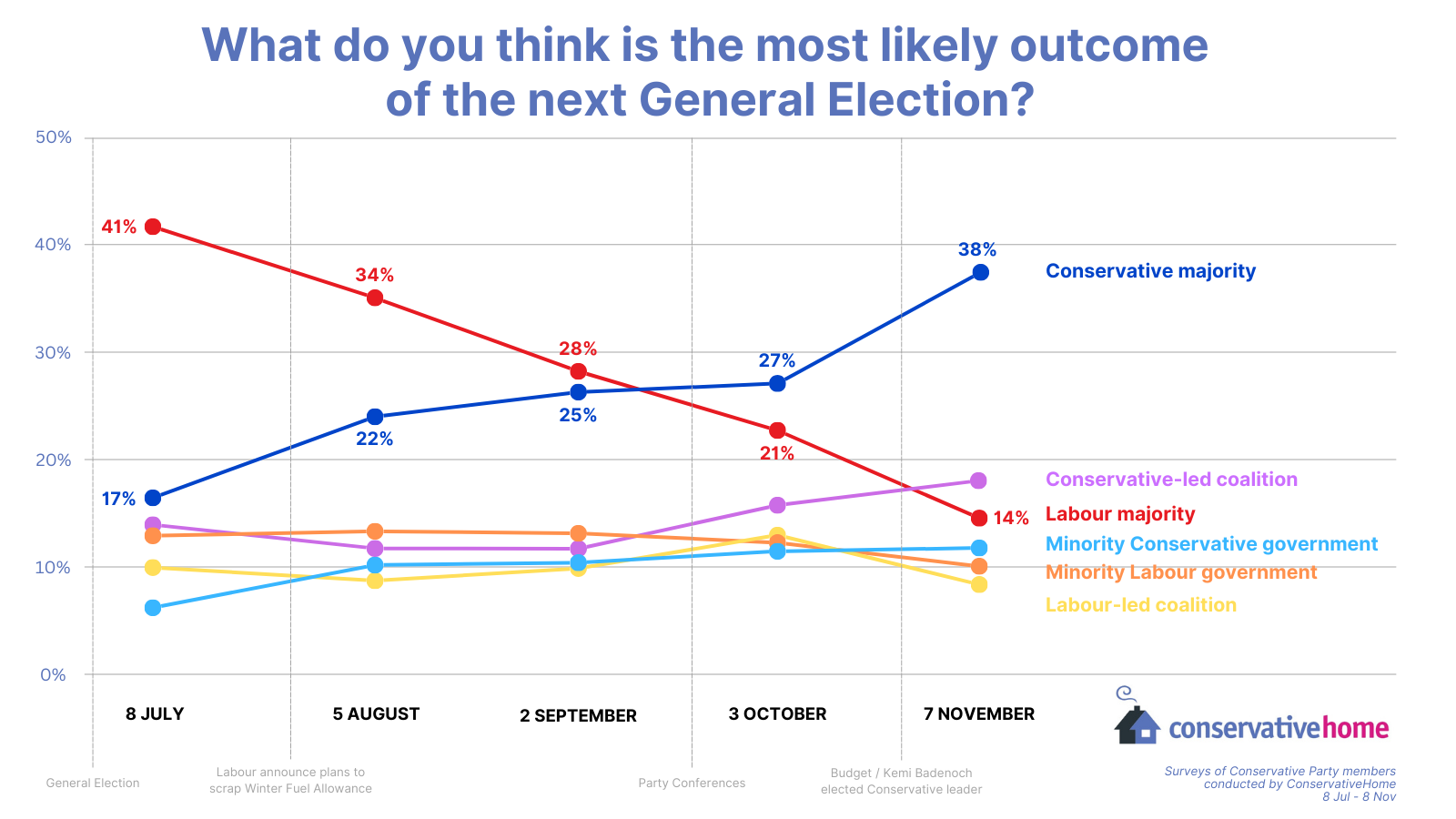

Every month, we ask a regular question of our panel about their expectations of the next election. Last time we checked in on it, in January, the outlook was understandably very bleak indeed.

But ten-and-a-half months is clearly a very long time in politics these days, for now no fewer than two thirds of respondents expect some kind of Conservative-led government after the next election – and more than a third expect the party to win outright!

That would be quite the turn-up for the history books, even if one suspects the smaller groups expecting a minority government (11 per cent) or a Conservative-led coalition (18 per cent) have slightly better odds if they fancy having a flutter on their expectations.

Before we indulge ourselves on what-ifs, a quick reality check: the odds of the Party returning to office in a single term are phenomenally long. As David Gauke notes in his column today, Tory polling in the middle of a parliament is no sure guide to the next election.

Furthermore, even in the event that Labour does contrive to lose power, it doesn’t follow that the electorate would swing back to us. There are the Liberal Democrats, of course, and then Reform UK, nearly all of whose second-place finishes in July were in seats that currently boast a Labour MP.

Long odds are not zero odds, though. The last election was an historic rout, but also a reminder that past performance is no guarantee of future events. Imagine telling anyone in January 2020 that not only would Labour be back next time, but with one of the largest majorities in the long history of our Parliament.

It’s also true that in terms of individual seat majorities, this is the most marginal parliament since the War. A swing from Labour to the Conservatives of just a couple of points could deliver up to a hundred extra seats – enough, perhaps, to let the incumbent Tory leader have another bite at the cherry, although still leaving the Party with an historically-unimpressive 220-odd MPs.

But slim odds of a happy fortune tend to grow in the imagination, so it’s worth also dwelling on two dangers that this finding (regardless of its accuracy) poses for Kemi Badenoch and the Party.

First is complacency. As I’ve noted before, she was elected leader on a unity ticket when Tory MPs are fundamentally disunited on the big questions facing the party. Many of the grandees praising Badenoch’s focus on ‘values’ were, frankly, people who profoundly disagreed with Robert Jenrick on the specifics of policy without having any better answers themselves.

If Labour continues to have a miserable time in office, the temptation will be great to sit back, pick some opportunistic fights, and let them defeat themselves, sticking to feel-good tunes about tax cuts that somehow don’t involve spending cuts. The problem with that is that even if it worked, it would only place our Party back in the very trap which is grinding the Government to paste.

As an amateur constitutional nerd, far be it from me to decry Badenoch’s current emphasis on “the need to develop a comprehensive plan to reprogramme the British state”. Process is important, and Britain’s processes aren’t good.

But elections aren’t won on process. If you want voters to take any interest in taking a hatchet to the state, it has to be in aid of delivering a policy agenda they care about. Formulating that, given the current state of the Party and Badenoch’s deliberately hazy leadership pitch, will be a delicate operation.

The second problem is more specifically hers: high expectations have to be met. If the membership was profoundly pessimistic about the amount of ground we could reasonably expect to make up in five years, the Leader would have more leeway for her preferred, low-profile approach.

Optimism is more dangerous. We suggested a couple of weeks ago that the critical test for the Government will come in 2026, when the front-loaded spending in Rachel Reeves’ five-year plan runs out – and that this would be the moment of danger for Badenoch too:

“If the Conservative Party has done the work, it might be the first opportunity it has to fight its way into the conversation and present itself as a credible alternative.

“But danger attends that opportunity. If the moment is missed – if the Government is really struggling but the Tories aren’t able to capitalise on it – then that might be the point at which restive MPs start sketching out their letters to Bob Blackman.”

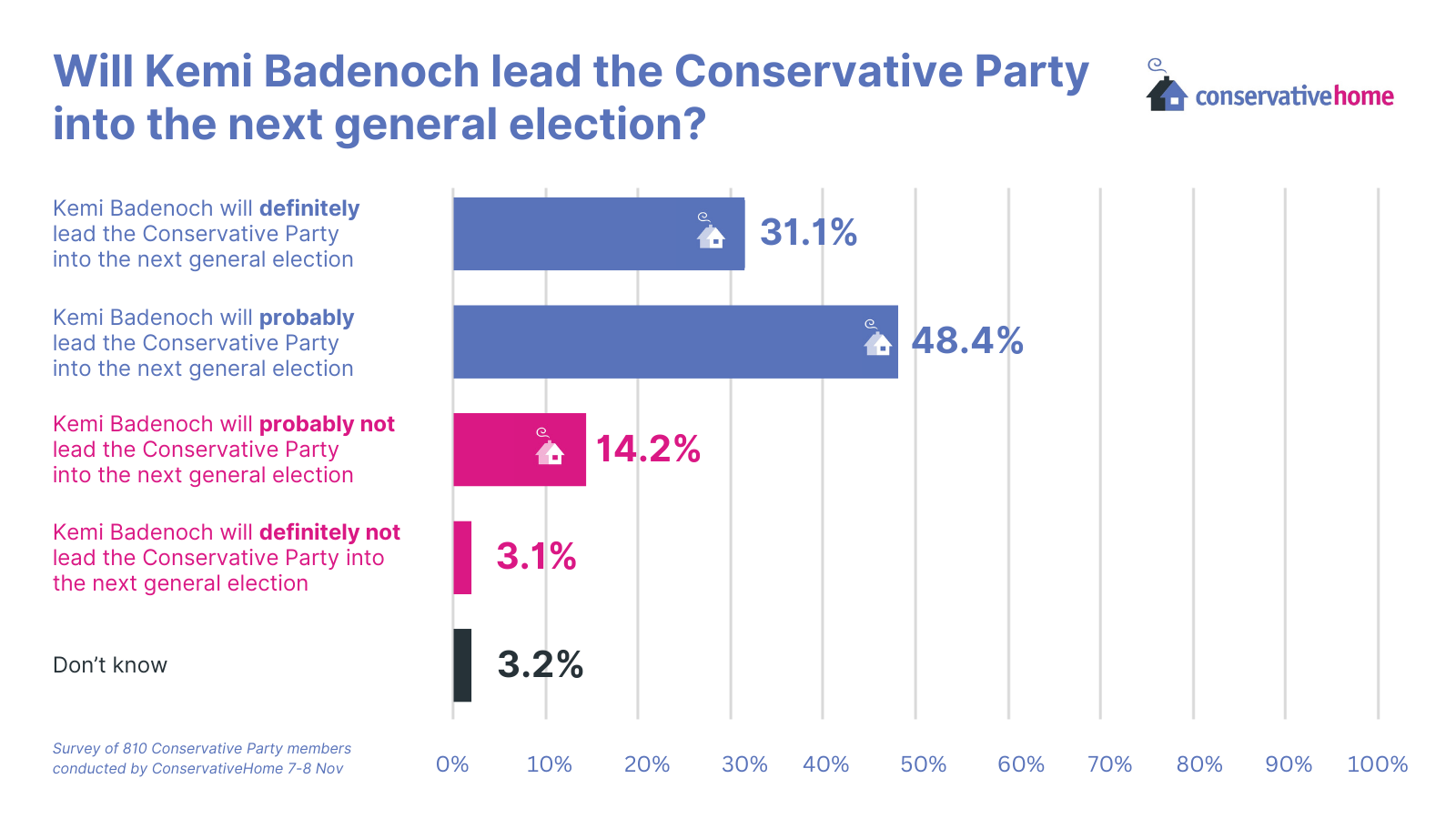

Perhaps that’s why less than a third of our panel think that she will definitely lead the party into the next election (see below graphic).

This isn’t a catastrophic result, by any measure. The combined total who think she will definitely or probably fight a 2028 or 2029 election is almost four in five; outright sceptics are few. Likewise, much of this is likely less a comment on Badenoch personally than simply a reflection of how assiduous the Party has been in disposing of its leaders in recent years.

Nonetheless, although they are yet some distance away, the shoals are visible beneath the surf. That leaves plenty of time to chart a course around them. But charting a course requires making definite decisions about your direction of travel.

The post Our survey. Four in ten members expect a Conservative majority after the next election. appeared first on Conservative Home.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·