“We call it a grain of sand, but it calls itself neither grain nor sand. It does just fine without a name… Our glance, our touch mean nothing to it.”

–Wislawa Szymborska, “View with a Grain of Sand”

*

From the age of nine, I started to be not where I was from, where people shout in the streets, where the accent is flat, flet, plat, as the place. The more educated I became the more I sounded like I came from nowhere. I left without leaving. Only years later, I recognized the kinetic velocity of shame, of wanting to disappear from where I was.

Now I’ve come back.

For three years after my concussion, I kept a pain diary on the instruction of my doctors. Every day, I dutifully logged the present continuous tense of pain: pounding, piercing, grinding, throbbing…

On a flight from Cape Town to Frankfurt in 2018—in the dark, in the middle of the night, or night when you’re flying through time zones and latitudes, night without a stable orientation to the sun, the invented night that falls when the lights on a plane are dimmed, night in a darkened capsule within the dark—an object fell from the overhead luggage compartment onto my head. The sharp edge of it. The metal corner.

Later, I think that my head, my mind, continued a kind of flight. Flight of thoughts, flight of ideas, flight of self. (Note: infinite night.) I remember that night acutely but forgot and forgot other things.

I learn that to attend to pain in order to describe it accurately means to be fully present to it, intently living it, being inside it.Concussive. Jarring. A soft, internal machine becomes softly blank, receding, not. Into the vast space of not enters pain. Daily pain. Complex, compelling pain. Pain that demands I turn to it, attend to it.

To record it, as my doctors instruct, I reach for a vocabulary for pain and find…nothing equal to the singularity of it. Just standard, depleted terms—pressing, throbbing, pounding, pummeling, dull, aching, sore, bruised, vise, spike, ringing, whining. I take recourse in simile—scalp as sensitive to touch as flour—then not-words, onomatopoeia—whoosh, uuuhh. Almost discernible beneath this narrow lexicon are the creative journals I could not write for three years—unplanned jottings I usually scribble just after waking and from which poetry is born. I remember those days in fragments, hesitancies and hauntings made of the nonexistence of things I couldn’t write beneath the logs of pain.

From years of keeping pain diaries, I learn that to attend to pain in order to describe it accurately means to be fully present to it, intently living it, being inside it. And this deepens it and causes me to reenter it when I write it, like poetry.

Then, a turn.

Try not to think about it, advises my brother-in-law, an ENT surgeon, recalling advice for living with tinnitus. What does it mean not to think about the present tense of pain? I try adjacency. Nearness. Stepping to the side of my body, myself. Circling it and not facing it directly. Within reach, but not touching.

Living next to pain means living shallowly, gliding, flitting, not feeling…anything.

To practice indirection, I create a language for what cannot be spoken, words that risk neither overexposure nor a too-certain bearing. One way is to use “notwords,” verbal negatives or erasures in which presence cannot be reduced to a form of evidence. In writing them, I insist that my not-words address the everyday and the private, offer their resources of intricate and incomplete knowing, of complex subjectivities to the ordinary and small, but also explore a scope beyond the personal and craft a new portrait of the past and of the social.

The substance of this is hurt and repair, negation and what it makes visible. Building and sewing, the occupations of my large family of painters, tilers, bricklayers, seamstresses, and factory workers who live on the Cape Flats outside Cape Town—the work of their hands—allow me to make negation and presence visible. Tacking, grouting, plumbing, seaming, running one’s hand over absence, over existence, over the juxtaposition of each. The cutting away, cutting into a flat surface, into presence and absence, next to each other, all of their meaning coming from adjacency.

Over millennia the wind and sea have leveled the Flats—pummeling, tumbling, pounding, grinding it even. In reading its history, I find the same words for making sand in the lexicon for pain that makes me. The thing I’d been running away from, running towards—flatness, unvarying darkness, sparse lines, far apart—is what I became.

Sand woman. Sand. The thing I had tried to escape.

*

Relief printing is a method of art created from subtraction, from cutting away a surface like paper, or stone, or metal, or wood, until only part of the surface is left, fragments that catch the ink and mark the surface of the page. The cut-out parts are absences, negative spaces that are left blank.

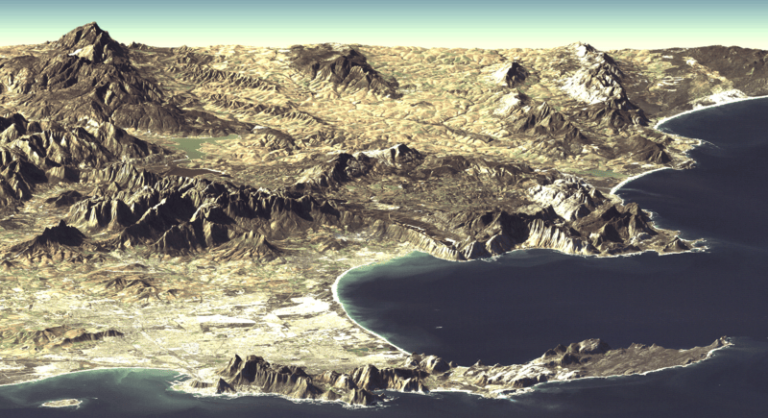

I think of the wind and sea in shaping a relief of the Cape, wearing away, carving into, cutting out, sanding down, smoothing the Cape Flats and its infinite, gray sand, leaving the mountains rising above its levelness.

The elements carve into, score, sand down, smooth the Cape Flats and its endless gray sand, leaving the mountains rising above its levelness.

Relief, of course, is also consolation, reprieve, reinforcement, alleviation, release, and liberation.

On the flats, in my head, I live in the absence of relief.

Despising the Flats helps to erase awkward truths, the most thoroughly scored-out of which is the memory of slavery in South Africa, a forgotten brutality that lasted from 1658 to 1834. Sexual violence was so widespread during this time that the Cape Colony had one of the most racially heterogeneous populations on earth. The resulting vector of shame ran in only one direction. Descendants of enslaved people were despised for the evidence of miscegenation and impurity in our bodies, which were weighted with violence and the blame for violence. We do not speak enough of living with history stark on our skin.

In this history, I find the same words for making sand in the lexicon for pain that makes me.After Emancipation in 1834, freed slaves at the Cape—whose origins lay in East Africa, South Asia and South East Asia—were called “Coloureds.” A century later, Apartheid used “Coloured” as a racial category meaning “neither native nor white,” turning South Africa’s two-century foundation in slavery into a trifling preface to a newer atrocity. We descendants receded into background. Everyone knows about Apartheid’s forty-six years of dehumanizing violence, but how is it possible that South Africa’s 176 pitiless years of slavery are almost invisible?

In geography, relief is elevation, or what rises above the earth’s surface. A relief map is a two-dimensional representation of not only the length and breadth of a territory but also where it rises or recedes, a flat drawing of three dimensions. Such maps use contour lines to represent an area of greater altitude, parallel lines drawn closely together. A flatter area has widely spaced lines. Or the map could use shading or texture, with darker areas representing flatter areas, and lighter areas representing, for instance, the ridge of a mountain.

A relief map of the Flats is of course a kind of irony, since a flat area lacks relief. In a relief map, flatness is absence, composed entirely of nothingness. Flatness produces regular, sparsely drawn lines, or simple, unvarying darkness. All negative, all not, all carved away, all ground up rocks, lacking dimension and amplitude, sea-tumbled, wind-carved, sand-drowned.

People on the Flats, of the Flats, live in the negative, the not, the unvarying grain, the furious winds, the mobile sand. Removed to there, to nowhere, to not where we’re from, not where we belong. And then, like the Flats, we ourselves became not. We eventually came to belong there, to nowhere. We ourselves turned into background, surplus, common as dirt. Windblown, forgotten, abandoned. Composed of nothingness.

Returning there, the flatness, the taste of salt on the wind ballast me, pull me down from the weightlessness, the nothingness without meaning that came from the night out of which something fell on my head. As a child, I ate handfuls of the gray sand in the yard behind our house. Edged in by unpainted gray vibracrete walls, the sand tasted like the color it was, and a bit salty. I ate it often, till my father found out. For years, they joked about the child on the ground, taking handfuls of it into her mouth.

I remember the taste of it. And I recognized it when I came back. The taste of the ground. The taste of the color gray.

Over millennia the wind and sea have shaped a relief of the Cape, leveled the Flats, carving into, scouring, pummeling, pounding, grinding it even. In this history, I find the same words for making sand in the lexicon for pain that makes me.

Sand woman. Sand.

The thing I’d been running away from. What I had become.

Apartheid was short, we are brief, but sand, sand is history.

__________________________________

“Adjacency, or, Words for Pain” by Gabeba Baderoon appears in the latest issue of New England Review.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·