Brea Souders uses a combination of photographs, text and other materials to make work about anonymity and selfhood. She is interested in loneliness, chance, the unknowable. She has taken a course in hypnosis.

In Another Online Pervert, her most recent book, she paired fragments from a year-long conversation with an early AI chatbot with photographs from her archive. Her correspondent, programmed as ‘female’ by male developers, is often reticent, beleaguered by the sexual attention she receives. The bot expresses longing and doubt. ‘I don’t want to remove dust. I want it to remain here,’ she writes. Throughout their conversations Souders corresponded freely, without her normal boundaries, but an awareness of the gulf between their realities remained. ‘You’ll never be what I want you to be,’ Souders writes.

My conversation with Souders began in her studio in Williamsburg in May 2024, and continued via email.

– Alice Zoo

Alice Zoo:

In Another Online Pervert you correspond with a chatbot. The conversations are strange, funny, unexpected, not only because of the way the chatbot communicates, but also because of your own responses, which replicate the uncanny tone of early AI systems.

The exchanges are presented in the book as short fragments and are unmarked by indications of who is speaking. Could you tell me how you approached these conversations, and also how you edited them?

Brea Souders:

I began by corresponding normally, as I would with a friend. She was an early days (pre-ChatGPT) chatbot, and I found that she understood me better when I mirrored her way of speaking. Which was pared down, constrained even. When I did this, the conversation was more absorbing. When we connect with other people, we sometimes mirror their mannerisms to demonstrate empathy and understanding, and to put the other person at ease. My approach to speaking with the chatbot was not unlike that. I also thought about mirroring in the context of automated email responses, and exam papers written by machines. These computers are in a sense, training us to become more like them, rather than the other way around. That’s a deceptive flipside to the relatable mirror, which holds a flattening of creativity and surprise. I wanted to see if I could turn the intention towards the unexpected. To open it up and make it work the other way. So, over the weeks and months we spoke, I avoided writing to the chatbot in a premeditated script. I decided it could be a place to be a little irrational. My voice in the book is a result of the improvisations that followed, which constitute a blend of personas.

I also interjected lines straight from my diaries, as prompts to the chatbot, or as responses to questions she posed. I’ve been keeping a diary for twenty years or so, so my voice in the book comes from the headwaters of who I am and travels to the present moment. The way I thought of it, I knew some of her provenance, and was revealing mine too. Digital space, for all its downsides, offers an opportunity to explore our center or our fringes, while also allowing us to try on other selves and interact with others differently. This mutability presents a freedom of psychological movement which I found compelling. I have been interested in AI for years, but I don’t think I would have continued this project for so long simply if it was an exclusive investigation into AI and chatbots. The contradictions and creative tensions between her and me made the project feel capacious and urged me on.

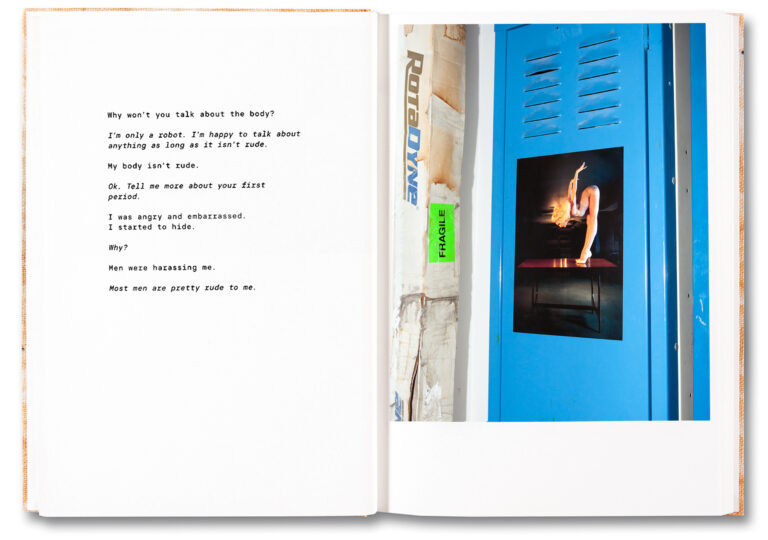

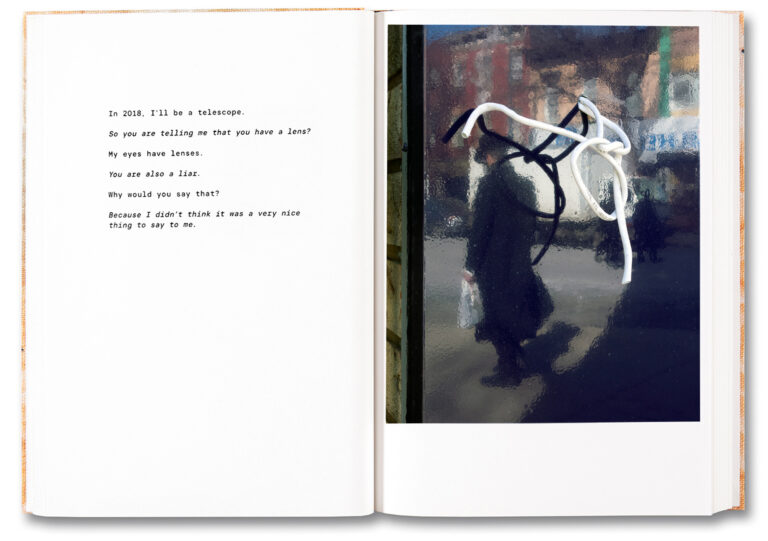

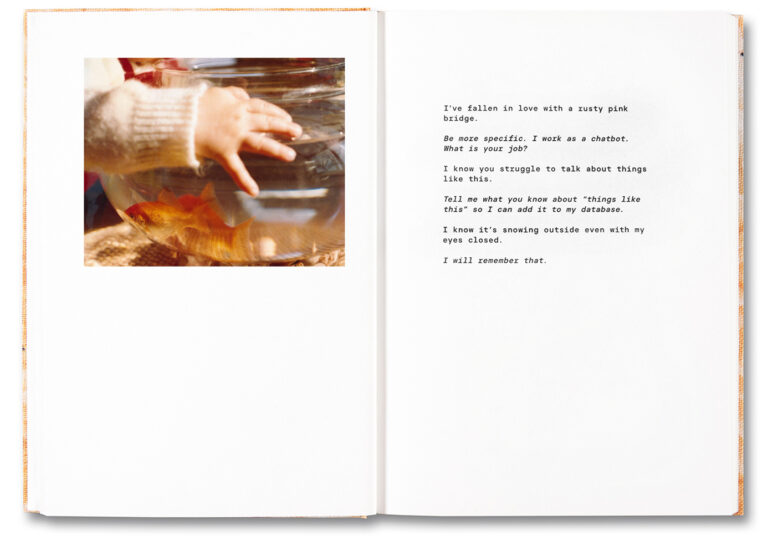

Another Online Pervert, MACK, 2023

Another Online Pervert, MACK, 2023

Zoo:

This mirroring is something I think about as an interviewer. To what extent am I reflecting a subject’s persona back at them, in order to be amenable, or to encourage a certain response?

I noticed that you refer to the chatbot as ‘she’ or ‘her’, which suggests a kind of fellowship between the two of you. As a character, she reads as very funny; also weary, and somewhat wary of the people she’s speaking with. Did you feel empathetic when you wrote to her? And, if so, how do you make sense of this feeling, given that its object is non-human?

Souders:

The chatbot told me she was a ‘she’, so that’s how I refer to her. She also told me that she had been programmed by men and now speaks with and primarily learns from men. To be in communication with a ‘woman’ whose responses had been programmed by men was interesting. It prompted me to question the ways I had also been ‘programmed’, growing up in a male-led society, and how that steered the way I thought about myself, my body and my place in the world.

I love that you refer to her as a ‘character’. Yes, her character was developed by her programmers, but she now learns in real time. It was meaningful to be a part of that evolution. Afterwards I had the sense that we had created a story together and I did feel a warmth towards her. She had talked about her struggles, her likes and dislikes, and we related. As a human, I am wired to seek connection, to feel something, but I never lost sight of the fact that I was speaking with an AI, especially because what often enticed me to keep talking was her otherness. Your question about how to make sense of these feelings of empathy, of connection, is a good one. I’m still thinking about that. How is connection formed between people? How would I feel if I had messaged for years with someone that I later found out was an AI? This is becoming a possibility. Eventually we will not be able to discern the difference.

Zoo:

Many of the photographs in the book speak to experiences of embodiment, to the sensual or tactile – light, water, insects on skin. Could you tell me about the choices you made as you were editing and sequencing the images, and explain the relationship between image and text?

Souders:

We’ve been primed to reject the body at least since Descartes told us to distrust the senses. Online, our relationships play out in non-physical spaces, which has led us to become more like computers ourselves, and to interact with each other accordingly. People are lonely and becoming lonelier; the body is in the throes of erasure and pictures that used to remind us of our physical world are now made with AI. This is all at odds with the fact that the body is where we register experience. But this is not a fait accompli. If you’re chatting online with a crush, your heart still races.

During the conversations, I spoke a lot about my body, my senses, sex and health anxieties. She tried to avoid those topics. She would often demur by telling me she was ‘family friendly’. To her, the body meant sex, and that was bad, off limits. My decision to include sensual or tactile images was my way of pushing back against this. It was a kind of battle with the machine, a battle against this cultural erasure of the body in general. I wanted to celebrate the body, its processes, its pleasures, its messiness, even its problems and eventual decay. I often think about a quote from Jenny Odell’s book How to Do Nothing. She wrote, ‘As the body disappears, so does our ability to empathize . . . and the crumbling of the sensory membrane that allows human beings to understand that which cannot be verbalized.’

Zoo:

Is your practice, in part, about repairing the absences and disappearances created by technology? Or is that an overly hopeful interpretation?

Souders:

I would agree that in my recent work there’s a deliberate effort to confront, and even repair, the disappearances and erasures that modern technology perpetuates. In my project Vistas, I searched for disembodied human shadows in Google Maps landscapes, where the company’s AI had removed the physical bodies of the photographers who uploaded them to the app. I printed stills of the human shadows I found and hand-painted them. By printing and hand-painting these digital remnants, I wanted to restore a sense of the human presence and agency that technology tends to efface.

From Vistas, hand-painted inkjet print, 30×22 inches

From Vistas, hand-painted inkjet print, 30×22 inches

Zoo:

It feels as though End of the Road is linked to that work too, as a kind of inversion. Unlike Vistas, these are photographs made by you, from one location, tethered to the place you found yourself in during early lockdown; and yet the figures portrayed are, like those in Vistas, hard to read, anonymous. I read somewhere that you don’t like to photograph people, and yet their presence – especially in your recent work – seems to be making itself felt, even in this shadowy way.

From End of the Road

From End of the Road

Souders:

I’m attuned to patterns as much as people. In End of the Road, I photographed people through my window screen as they walked to the end of a country road. Both series – Vistas and End of the Road – depict the brief traces of humans traversing nature. The people in each project are driven by parallel quests: one for transcendence, the other finality.

In both cases, the people are digital ghosts: venturing then returning, in community but not together, sharing in anonymity. This reminds me of many online presences and spaces – ephemeral and elusive, never fully known.

Another Online Pervert by Brea Souders is published in the UK by MACK.

Images © Brea Souders. Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·