How can you write freely and release any blocks that are holding you back? How can you focus on the strengths in your writing and avoid critical voice? Robin Finn gives plenty of writing tips in this interview.

In the intro, KDP's identity verification; Why authors need platforms [Kathleen Schmidt]; Romance genre report from K-lytics; Canva has bought Leonardo AI image generator.

Plus, join me and Orna Ross for a writing retreat near Dublin, Ireland 11-13 April 2025 [More details here; Kickstarter Rewards]

Today’s show is sponsored by Findaway Voices by Spotify, the platform for independent authors who want to unlock the world’s largest audiobook platforms. Take your audiobook everywhere to earn everywhere with Findaway Voices by Spotify. Go to findawayvoices.com/penn to publish your next audiobook project.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

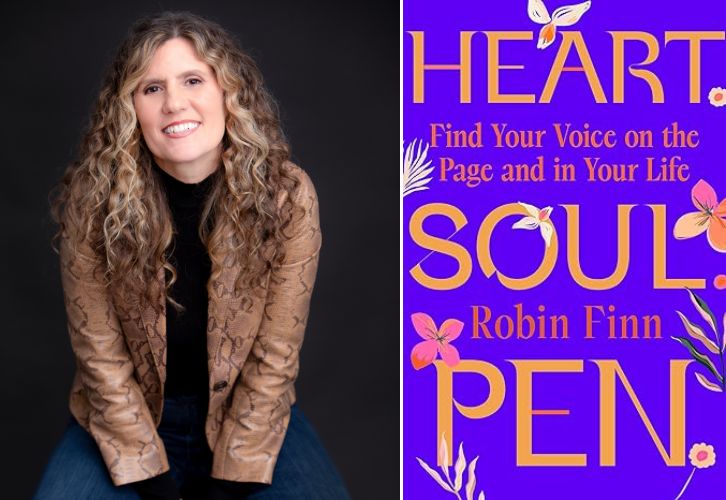

Robin Finn is an award-winning writer, teacher, and coach, and the author of Heart. Soul. Pen.: Find Your Voice on the Page and In Your Life.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

Overcoming the fear of judgement and shame when writing Uncovering the different layers of limiting beliefs Valuing our writing across all genres and topics Strengths-based feedback and how to use it Using the TIDES principle in the critique process Tapping into your curiosity to find your author voice The magic that can come from timed writing Practicing the art of discernment in your writing and sharing Benefits of an in-person writing communityYou can find Robin at RobinFinn.com and on Instagram @RobinFinnAuthor.

Transcript of Interview with Robin Finn

Joanna: Robin Finn is an award-winning writer, teacher, and coach, and the author of Heart. Soul. Pen.: Find Your Voice on the Page and In Your Life. So welcome to the show, Robin.

Robin: Thank you so much for having me.

Joanna: I'm excited to talk to you today. So first up—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing and publishing.

Robin: Well, my story is a little meandering. I really was a writer when I was a child, but I sort of tucked that away for decades.

Then years later, after I became a mom, I had a child with severe hyperactivity. It made parenting so difficult and excruciating, particularly the judgment that I got from all the other parents, that I ultimately ended up writing as a means of healing.

I wrote, originally, a lot of personal essays about parenting a child with special needs. That was really the beginning of my writing career.

During the time when I was really actively parenting and really struggling, I ended up going back to school and getting a master's degree in spiritual psychology. Spiritual psychology is a program where you really connect to what is your purpose. One of the things that came out of that program for me is that I'm a writer. So I started to write about parenting a child with special needs.

I was really scared. I had a lot of shame and a lot of judgment about what I was writing.

I went to a conference, and I met some writers, and I decided I'm going to send out one of my essays. To my shock, it was accepted. Then when I saw it online, I was so shocked and scared, but what happened from that point was I was flooded with emails from other parents, really, Jo, from all over the world.

From Australia and Japan, thanking me for writing this piece and telling me they were having a similar experience. That connecting with others and realizing how healing writing can be, not just for myself, but for other people, really spurred me on to publish my work.

Then from there, it was really, again, like I was reached out to by so many women asking me about writing and about how they also were having experiences they wanted to write about.

So I sort of blended my background in public health, spiritual psychology and writing, and I created this program called “Heart. Soul. Pen.” for women writers to find their voice. I taught this program for many years, and then ultimately, it became the book.

Joanna: That's so lovely for you to share those feelings. It really strikes me. We've only been on the phone like three minutes, and you've used the words judgment, shame, scared, shocked. These are all really emotional words to use about writing.

I know there's people listening, I've certainly felt it myself, I wrote a book last year—well, it was written over a long time, I published it last year—called Writing the Shadow, which is based on the Jungian idea of Shadow. I cut some things out of that book because of some of those things you're talking about. So if people listening feel the same thing, they feel that fear of judgment, they feel that shame—

How did you get past those things in order to share that first essay?

Like that first step before you got the feedback, how did you do that?

Robin: Well, it's a really good question because when I was writing the book, Heart. Soul. Pen., I had been teaching “Heart. Soul. Pen.” for years, but I literally didn't know what it was I was teaching.

It's such an intuitive process that I had to be like, okay, wait, how can I make into a system what I'm doing? It's interesting you bring this up, because the first step of the book is called “Revise and Release Limiting Beliefs.” That's step one.

I literally take you through how I did that with parenting and how it really applied to writing. This idea of writing down what I believed about myself as a mother.

That was the despair that brought me to spiritual psychology school was this idea that I was a failure as a mother because I couldn't fix my son and I couldn't fix my family and make them into this perfect fantasy family.

I had to go through this entire process of writing down what my beliefs were about myself, and then really asking myself, do I even believe my beliefs?

Also asking myself, do these beliefs support me having a joyful, peaceful parenting life? And they really did not.

Then being willing to rewrite the beliefs and then repeat them every day until eventually over time, they became my new belief system.

When I started writing, I literally went back to that very same process, and I outlined it in the book. It is a step-by-step process of being willing to start with examining what do you believe about writing, and about worthiness, and about your own voice, and being willing to write it down and look at it.

I can tell you that a lot of things I believed about my own writing and my own voice were just dumb, just silly. I didn't even believe my own beliefs, but they were there inside of me.

Then being willing to review them and ask myself, if I believe I don't have anything important to say, for example, does that support my goal of writing? Not really.

Am I willing to let that go and replace it with a different belief?

For example, what I have to say is helpful to myself and to others. Writing is a part of who I am. My message is important.

Replacing it with beliefs that support my goals, and then being willing to look at these new beliefs every day, maybe multiple times a day, until they really become my new belief system.

I think for all writers and creatives to be willing to do that step before pen ever goes to paper is so powerful and life changing. I truly believe that.

Joanna: It's interesting. It's a very difficult thing to do, though. You open the book with something that resonated with me, you said, and this is a quote from the book,

“The messages we receive as kids get lodged inside of us and become lifelong limiting beliefs that impact how we live, work, write, create, show up in our lives and relate to others and ourselves.”

It's so interesting because I actually put my experience of school in that book Writing the Shadow, where a teacher basically told me that I couldn't write that kind of thing. That it was too dark, that it was like a nightmare. I shouldn't write that, I should write something nice.

“Write something nice” has sort of become something I resist now. I write dark fiction, for example. It's so interesting, it took me many, many decades to uncover that. So I guess I'm asking—Are these limiting beliefs layers?

So we uncover something that might be obvious, but it takes a while to get down to the lower limiting beliefs.

Robin: Yes. I really love what you're sharing. I can't tell you how many students come to my classes, how many writers with stories like that. I talk about this in the book, how women often feel like, “My writing has to be pretty, my writing has to be good, my writing has to be sunshine and roses,” like what you're saying.

These are not true. These are the types of beliefs that gets stuck inside, and it's very difficult to write when we hold these beliefs. It's not impossible, but I call it “writing through mud.” You can do it, but it's so arduous.

Isn't it more fun to write with flow, to just have the words fall out? Well, if we want to have that kind of flow, we have to be willing to excavate at least a little bit of these limiting beliefs. To your point, they are very layered, but we've got to start somewhere.

In the book, I don't dive into the deepest layers, but I start with how can we look at just the top layer of what we believe about our voice, and our writing, and our worthiness, and start to loosen that up a little bit and create beliefs that really support us in our writing journey?

That's nine tenths of getting rid of the barriers to writing is to let go of these beliefs that what you have to say is too dark, isn't important, is wrong in some way, is shameful. None of that is true.

Joanna: Another thing you raise, you mentioned purpose before, and writing is a purpose.

Many of us think our work is just pointless, or maybe it's boring, or it's been said before, or maybe it seems frivolous in a world where we should be writing something very important, something political, or about health, or something where it's more important than a fictional story.

I mean, sometimes I feel that, and you talk about this myth of the mundane in the book, which I like.

How can we value our writing, whatever that turns out to be?

Robin: I think that's a really beautiful question. One of the things that I do is I offer lots of opportunities to write in community, whether you take a writing class, a course, or a workshop.

Writing in a community that particularly offers strength-based feedback and not critique is so empowering for the writer to see how deeply resonant their words are. It is not true that your daily life is not important. So much of what life is about is the daily aspects of living, and they're metaphors for so much more.

So this idea that writing about my life because I didn't climb Mount Everest isn't important is, again, just a limiting belief, and it's not true.

I had a woman once who wrote about how she had to make chicken and rice every single night for dinner because her kids only ate chicken and rice. When she read the piece, people teared up because it wasn't really about cooking chicken and rice.

It's about someone who loved to cook as an art, and what a prison it felt like to have to make the same meal over and over again, and about wanting to be liberated. It was about so much.

I think the writer would have judged it as not important if they weren't in an environment where they were able to hear from other writers how resonant their story was.

So I do think writing in community where you get an opportunity to hear comments on your work that focus on the strengths and the resonance of your work really helps a writer see how powerful their words are.

Joanna: Yes, and this is obviously one of the keys to good writing is being very specific. Like you mentioned there the chicken and rice, and in my head, I could kind of see that woman reading this and see the sort of bland food she was putting out there.

Writing about that specific situation, as you said, the other people, the readers and the listeners, will bring their own meaning to that. I was thinking it was a form of sacrifice that she was doing this for her family. That, again, it's a universal feeling.

So I love how you explained that. Writing your specific things, other people will turn that into their own message.

Robin: Other people will turn it into their own message, and it will reach the people for whom that message is so deeply meaningful.

The other thing is, the writer doesn't see the value. So letting other people respond to this piece about chicken and rice saying, “Oh my god, motherhood has also felt for me like a prison,” or, “The repetition is so difficult,” or whatever it is that it brings up for other people.

It helps the writer understand that, wow, what I have to say is important and very layered. To judge it as dumb or mundane and then throw away my paper, you're denying everybody the power of your words.

Joanna: So you mentioned a few minutes ago, ‘strengths-based feedback.' All writers have this inner critic and we tear ourselves apart. We also have editors, and readers, and reviewers who also tear our work apart. So we often come from a negative feedback point of view.

Could you explain strengths-based feedback and how we might put that into practice?

Robin: Well, as a teacher and a workshop facilitator, it's really my deepest belief that writers get critical feedback way too early, and I strongly am opposed to that. I think there is a place for critical feedback, but it's much, much later in the writing process.

Most writers they get excited, and then they get feedback, and what happens is the critical feedback really ruins the joy of expression. It confuses us, and it disconnects us from that thread that we're just getting of the story. So I really, really caution writers to not receive critical feedback early on in the work.

Strengths-based feedback really has to do with sharing with the writer what is working in the piece, what is resonant about the piece, what you notice about the piece, and where you might have questions.

I have a little acronym, following the TIDES. That's T-I-D-E-S. that's where you just focus on the themes, images, details, emotions, and structure of a piece.

So for example, someone might read the piece about the chicken and rice, and a fellow writer might say, “The images were so clear to me. I could see the kids sitting at the table. I love the detail about the type of rice she used,” or, “The emotions of how weighty this was for the writer, I really felt the emotions.”

So we share what we notice about the TIDES, and we don't get into the critique. I think that's really important because the place for critique, in my opinion, is much, much later in the writing process.

Joanna: It's really interesting. You talk about writing community, I never do that. I have never been in a writing group because I like being on my own. Also, as you say, I feel too vulnerable. I don't trust that people in a writing group, other writers, understand what you're talking about, for example.

Actually, as writers, we're not normal readers. We instinctively criticize because we've read so much or we've read across multiple genres. Often people might say to a romance writer, “Oh, that is too romantic. Why isn't it more literary?” or whatever.

So there'll be people listening who are in writers’ groups, and they would love their writers’ group to kind of follow this process. You talk about it in the book, obviously, but—

How can we shift that critique process into something more positive if people are in writing groups?

Or maybe they have to find other groups, basically.

Robin: Well, one thing I'd say is I have a whole section in the book devoted to strength-based feedback, following the TIDES. I go through in detail how to do it.

Of course, it's never too late. If you're in a writing group, and you want to try working with strength-based feedback, try looking at the TIDES of the work, you can certainly step by step, you'll learn how to do it in the book.

The other thing is just a quick litmus test for any writer, and I say this to all my students who I work with.

If you're in a writing group, and it makes you want to write less, it's not a good group.

If your writing group makes you want to write more, if your writing group makes you feel enthusiastic about writing, great. If you are in a writing group that makes you feel bad, want to write less, or hang up your pin, then that's just not a good group for you.

I just can't underscore enough how strongly I believe that everyone has a creative voice. People who are drawn to writing are drawn to writing because they're writers.

It is your responsibility to take care of your creative heart and to put yourself in a situation where you are supported and nurtured by the other writers you're working with. If that is not the case, then that is not a group that I would recommend for you.

Joanna: Yes, absolutely. Then, okay, assuming I'm in a group like that now, so say I'm the chicken and rice lady. The reality is maybe 80% of what I've written is not great. With the feedback you've given me on the TIDES principle, as the writer—

Should I focus on strengthening the positive side of things and just ignore fixing up anything people didn't mention?

Or do I just kind of leave that and move on? So I guess I'm asking the response of me, the writer, to that kind of feedback.

Robin: Yes. Well, I think when you read your piece, and you get notes, and people share with you the themes that really resonated, the images, the details, there's also something called trigger lines, where I believe in a piece of writing, there are lines that trigger deeper stories.

Sometimes that will be reflected to the writer too. “Like, wow, that line, ‘I never get what I want,' that was so deep. I'd love to know more about that.”

So I might say to the writer, “Circle that line, there's more there for you to explore.” So when you're done reading your piece, you'll have notes about what really resonated, where people were really moved, what lines maybe have more story.

You'll leave class knowing like, I think there's a whole other story hidden in here that I want, and I may feel very enthusiastic about working on that.

So it's not really a matter of like nothing else that wasn't mentioned matters. It's really just an arrow pointing the writer into, how can I go deeper into this story? How can I excavate further into really getting into the story that wants to be told?

Joanna: Of course, if people are doing this on their own, I mean, like something I do is I'll print it out on paper, and then I might find something and highlight that or underline something where I feel that in my own writing.

It strikes me that you must have a very keen ability to listen both to the words and to the meaning beneath the words. I'd love to know if that's something that you've learned how to do. Is that something you've particularly focused on, or is that something you think you've always had?

Robin: Oh, wow. No one's ever asked me that question before. I bring my whole self to the listening process, and I've been doing this now for a long time. I have honed a lot of these skills in this spiritual psychology realm of really listening not just to the words, but to the energy behind the words.

Also, when you focus your attention on these ideas of what resonates for you, it just becomes very clear. It's a process for sure you can do on your own. I mean, not everybody's going to be in a writing group.

I think that as you, the writer, start to look at your work, I talk about like a kaleidoscope, you shift the lens.

Instead of looking to criticize your work, you're asking yourself, what themes, images, details, emotions, or the structure, what do I notice about my work?

How can I be curious about my work? What can I discover from my work? Instead of looking to criticize your work, you can develop these skills yourself.

To your point, as the writer, you can feel as you reread your work, you can feel the lines that are kind of jumping off the page that want to be double clicked on. There's more story behind them.

You can feel it, and you can hone your own skills as you work with this idea of stopping the criticizing, stopping the judgments, stop the constant, “it's mundane, it's not good enough,” and shift into, “I am going to be curious about what I have to say, and where there might be more story for me.”

I believe for each writer, they'll start to have a different relationship with their own work, and it will start to flow more. It will become more clear what they really want to write about.

Joanna: You mentioned there about ‘feeling the lines,' and what resonates for you, and curiosity. I talk about these things as well.

Of course, in the book, you talk about finding your voice, but it's such a nebulous concept for new writers, in particular, who don't have creative confidence and are always second guessing.

How do people tap into that curiosity?

How can they try to feel the lines if they're listening to you going, well, I just don't know what that is?

Robin: I guess what I'd say is you could get the book and go through the steps. One of them is using a timer, writing faster than you think. Writing to a timer. If you're a new writer, set your timer for three minutes or five minutes, and write as quickly as possible.

The purpose of this is to write faster than you're thinking so that the words are emerging. You're not making them up in your head and putting them on paper, they're actually emerging from a deeper place.

As you do that, time after time, you start to reread your writing and see the themes that just naturally emerge. So if you're trying to find your voice, I'd say one easy way is to start with a regular writing practice where you set a timer, and it could be as little as three or five minutes a few times a week, and just freely write.

Then have an air of curiosity about what comes forward and you start to see what emerges naturally, what is your material. What you are concerned about, what matters to you, will naturally emerge if you get out of the way and allow it.

Joanna: What do you think about dictating as the process for free writing?

Robin: Well, I just came back from a wonderful workshop that I did in the Berkshire's, and the students there were all seniors, like over 70. It was a wonderful experience.

Some of the people, one woman in particular, couldn't type because she had a disability, so she would dictate. She was a poet. I thought it worked out for her really beautifully.

So I think it really depends on where you're most comfortable. If you're just starting out, I would say start with paper and pen. That whole tactile experience is so powerful.

If you can't use paper and pen, you can type. If you can't type, you can dictate. Like whatever works for you is what you should do. You should not allow a barrier to stop you from writing if you feel like you really want to express yourself that way. So I think that if dictating is what works best for you, then go for it.

Joanna: Yes, I do write in my journal for some things, but I never really write finished sentences.

I type my finished sentences, but my journals are full of fragments and just bits and bobs and ideas and quotes.

There's different times to do different things, but the core is in there somewhere.

Robin: I agree with you. I mean, generally speaking, I type on a laptop when I'm writing a book or I have the thread of an essay.

I also have periods of my own time where I'm like, I don't know what I want to write about, I've got nothing. So that's when I'll get out my trusty pen and my paper, and I just start writing pen and paper. That is the best way for me to try to connect to my own voice is through pen and paper.

Once I have the spark, and it's flooding, and I really want to get all these words down, I switch to my laptop. So to your point, I think there's different times in the creative process where different tools serve us best.

I'd say for new writers who are looking for their voice, looking for an idea, sometimes paper and pen is actually the most powerful.

Joanna: Yes, it's interesting, isn't it, because you do say your step four in your process is write faster than you think. I cannot write faster than I think by hand anymore, but I am really fast at typing.

So when I want to get into a flow state, I can't really do it by hand, but I can do it typing.

Robin: When I'm working with new writers and they're doing that step, and the timer goes off, they shake their hand out, “My hand hurts.”

I say to them, you actually did a beautiful job following the assignment, because it's true, your hand literally can hurt from just writing, writing, writing, writing as fast as you can.

For you, you may be at the place where you can't, and you just have to type. I get into that state sometimes too, where I just have to type. I really think the whole purpose of the book is to respect yourself as the expert of your creative process.

My best advice would be, follow your own guidance.

If you feel that you need to type, trust that you know best for you and type. If you feel you need to dictate, then dictate. The whole purpose of Heart. Soul. Pen. is for you, the writer, to trust that you're actually the expert of your creative process.

If you allow yourself to come forward as a writer and listen to your own guidance, you'll be amazed where it will take you. The steps in the book are really just me trying to break it down in ways that are easy to follow for each person to come to the awareness that they really are the expert of their own creative process.

Joanna: Yes, it's interesting. Timed writing, I think is magic. I also had my first sort of breakthrough at one of the many writing workshops I took in the early days before I wrote anything, really.

I would read all the books, and I'd go to all the talks, and then someone like you basically said, “Right, before I start my talk, we're all going to write together for three minutes.” The prompt was something like, “It was at that moment I knew.”

I still remember what I wrote, I won't go into it, but it was like, “At that moment, I knew.” I immediately was like, oh, what, we're meant to write?

What is so incredible is that — if you force yourself to write, like you say, with a timer for three minutes — it can change your life.

Because when you look at what you've written, you realize that you can do it.

That's almost the first step, isn't it, this sort of trusting what will come out if you then do another three minutes, or another hour, or whatever.

Robin: I agree with you. I do feel that timed writing is magic. The other thing that I do is I choose prompts that are really random. My favorite way to get prompts is I have each writer choose their own prompt. It could be something like, “Look around and name the first three things your eye falls on.”

Again, I believe that your eye falls on the first three things that speak to you, personally. Not the three things that I'm giving you, but the three things you notice in your experience, and then you have to put those in your writing.

So that forces our brain to have to make all these weird connections. How am I going to get blue stapler, yellow pen, and lipstick into my writing? Those are the first three things I saw. So our brain makes all these strange connections.

Then when people read their writing, it is very magical. There's something so authentic about it when you stop trying to create it and just allow it to emerge.

Joanna: Those connections, the connections that you make, even given those same prompts, you know, you and me and everyone listening, we could all write something.

Everyone's will be different because of who they are, where they're brought up, their background, their culture, their religion, like all of this stuff.

So that's why I always say to people, look, don't worry about writing another love story. You know, everyone has a love story, and everyone's is different. I mean, you must have seen this—How many variations on a prompt must you get in your workshops.

Robin: It's incredible. In the book, every chapter starts with a paragraph written by a different writer to the prompt, “I remember.” So there's 10 chapters, so there's 10 little mini pieces of writing.

They're all five minutes, and they all start with, “I remember.” As you read them, you can see how wildly different they are. Then at the end, I take you through each one of those chapter openers, and we follow the TIDES.

I talk about the themes, the images, the details, etc. in each piece and how wildly different they are. That's where I believe we all have unlimited creativity. We all have so much to say that's unique.

To your point, often writers will say to me, “Well, I don't think I should write my love story because there's so many love stories already written.” I just feel like, again, that's a limiting belief because your love story in your voice hasn't been written. No one can write that but you.

So it's not like you have to write something that's never been written before because your story in your unique voice is 100% new.

Joanna: Then over time, that's what readers come back for. I actually had a review this week, I wrote a short story, it's called De-Extinction of the Nephilim, and it's like a techno thriller with archaeological and religious elements. So it doesn't really fit in a genre.

Someone said, “Oh, I don't really read short stories, but I read this, and I can see the strands of J.F. Penn's voice in this story.”

It just thrilled me because I have had points of thinking, “Oh, I've written this before.” I've written about Nephilim before. I've written about angels before. I've written about this trope, or this. That's because that's what I love, and actually, that's what the readers come for because they love them, too.

Like there's lot of crypts and religious relics. Those are the things that come out in my themes. So I guess it's also about the confidence that you can still double down on those things, even if you've written about them before. It will still be in a slightly different way next time.

Robin: Absolutely, and I hear that a lot. You know, I am always writing about blame. Someone will tell me, “I'm just writing about divorce over and over again. I don't want to keep writing about divorce.” Well, you're going to write about divorce until you're done writing about divorce.

That might be a theme for you throughout your life, or it may just be a theme for now.

We are going to write about the things that are of interest to us for as long as they're of interest to us.

This idea that there's a deadline like, “Well, I've written about crypts, so now I have to write about something else,” but if that's what turns you on, and that's what's of interest to you, that's going to keep coming up. Instead of acting like it's a bad thing, we could just embrace it.

Joanna: Yes, and I think I got to that point, and just went, you know what, this is what I love, and this is what my readers love, and they will come back for this. So that's interesting.

As we carry on in the book, you had a really interesting bit about putting yourself out there. So this is a quote from the book.

“Discernment is the space between writing and sharing, where you stop and consider the next steps.”

“It is the process by which your thinking mind considers the possible outcomes of sharing your work and makes decisions about privacy, timing, and consequences.” This is so important because—

Everything you've said so far very much underscores the need to share personal things in our writing.

So how do we do this? Because people are very scared to put themselves out there in a world where social media can be hell, basically. We talk about judgment, I mean, there's a lot of it.

Robin: Well, so that's why I feel like really understanding discernment is really important. So there's writing, then there's discernment, then there's sharing.

So when you're in the writing phase and you want to be able to write freely, whether that means if you're writing nonfiction, you want to write about family matters, or things that have actually happened in your life.

Or maybe it's fiction, and you're writing sex scenes, or you're writing whatever it is that you want to write.

You have to allow yourself the free rein to write anything.

I think it's really important that writers understand that just because you write it, doesn't mean you're going to share it. We're going to move into that space between writing and sharing, where we are going to now use our discernment to decide what we're going to do with our work.

If when we write, and while we're writing we're trying to edit out things that we don't want to share, we really screw up the process. So it's really important to understand writing is that process that you and you alone do, and you can be fully free to write whatever it is that you want.

Then we go into discernment. Should I share this? Will my family get mad at me? Is this actually private material? Are there things that I want to edit out of this?

No, I don't want to share it. Maybe I only want to share it with certain people, but not widely. Maybe I want to share the whole thing, and I'm ready to throw a bomb in my life.

These are questions that are very personal to each writer. How much of what I have now written am I going to share? Maybe I'm going to fictionalize it. I mean, there's lots of questions about, is this the time? Is it private? What will these consequences be?

This is a thinking process that we have to go through after we're done free writing and giving ourselves full liberation to write whatever you want. We then have to go into the thinking part and ask ourselves, how do I feel about sharing this piece? What do I want to decide to do?

Then after we make those decisions, we get into the sharing. So I think it's really important to understand that—

Just because you wrote it, doesn't mean you're sharing it.

If you don't distinguish those two phases, if you don't distinguish them, you can end up trying to edit yourself as you write. I find that never works.

Joanna: Yes, definitely. I have struggled with that, as I said, in Writing the Shadow, and I had a memoir on pilgrimage where I mentioned menopause. At the time, I was like, do I really want to put this in a book? But I needed to write about it, and I was like, okay, I'm going to write about it.

In the end, I put a little bit, not too much, but it was something that really came up for me. Obviously, there's a lot of judgment in midlife, as you know.

I did want to ask you specifically about what you have done with that. Is it about the time that's passed? Because you started this interview talking about the difficulties in parenting your son. So you're admitting something there that perhaps has had an impact in your family.

How did you get to that point of sharing something so personal?

Robin: I guess I'd say I never wrote my son's experience because I'm not capable of doing that. I wrote my experience as a parent.

I always offered for my own children, anytime that they appeared in my writing, and really, my first love is personal essay, so I have written a lot about my family. Any child of mine that appears in my writing is always given the opportunity to read the essay and let me know if they don't want any part of it to be shared.

That's my decision as a mother that I would never want to write anything that any child of mine would interpret as betraying their confidence. So I always give my children the opportunity to read anything.

I still write about, to your point, midlife and empty nesting and different things that have happened with my young adult kids. So anytime they appear in my work, they're always given the opportunity to read it. If they have notes about it, I would certainly take their words.

That's most important to me, number one, is that I would never betray their confidence. Having said that, because I'm a writer, my children know that I'm going to write about our lives.

I literally have never had any of them ever ask me to change anything. I mean, that's just me and my family, but that is a part of discernment. Where for me, if I'm writing something personal about my experience in parenting and one of my kids appears, I want them to have the opportunity to read it.

That's a decision I've made, and so I do that before I share. That's part of like, I write anything I want, but then I do take that time to share it with them because their confidence is important to me. So that's one of the things I do.

Not everybody who writes personal essay wants to share every single thing they write about. I think you mentioned, Joanna, that in your book, there were things you took out. Maybe not just about menopause, but just other things.

I think that's important, where we then look at our work and decide like this may be too private for me. Once it's out there, it's out there. So you do have to really ask yourself those questions.

I feel that personally sharing the struggles I went through as a mom was so liberating. It helped me connect so much with others. I believe it was a service for both me and other people, but these are decisions that I think are really individual to each person.

Joanna: Yes, absolutely. You're right. I mean, there were things I'd written about people who were still alive, who I love, and I just decided that I didn't need to put that stuff in for the book to still serve the purpose that I wanted it to serve.

I think that's the other thing. You obviously have helped so many people with some of the words you've written around your parenting, and that's helped other parents. I felt with my book that I had served the purpose of the book with what I wanted to put out, and I didn't need the things that I had to potentially question.

So, yes, as you say, the discernment is a very personal thing. Your words can certainly change other people.

I do have one final question just before we finish. We're almost out of time. I wanted to come back to your live events. You've mentioned community, you work with groups of writers.

What is the benefit of being physically in the same space with writing workshops?

You might feel really vulnerable, but in this world of Zoom—you and I are now on Riverside—but with the online things that we do so much, what are the benefits of in-person writing?

Robin: Having the opportunity to share your work and know that the response to your work will be nurturing, because I create a safe space, so it is always nurturing.

So having the opportunity to share your work live and receive feedback that is strength-based is, I would say, transformational for the writer. You are seen, heard, and understood by other people, and you have the chance to hear what resonates for them about your work.

I'm not sure there's anything more inspiring for the writer. Any time that people come together live and write and share together in a framework that's strength based, I would say people leave exhilarated because it's this opportunity to take off our mask and really be seen.

I just can't say enough how much inspiration I feel like writers come away with. They come away with a feeling of my work matters, and I'm ready to dive into writing.

Joanna: Fantastic.

Where can people find you, and your books, and courses online?

Robin: I'm at RobinFinn.com online. I'm at RobinFinnAuthor on Instagram. My website, RobinFinn.com, I post all my events. I do online workshops. I do one evening events.

I really encourage people to come and write and share together. You'll be amazed at how inspired you will get.

The book is available everywhere. You can go to my website and see, but it's basically available everywhere that you buy books.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Robin. That was great.

Robin: Thank you so much for having me. It was really fun to talk to you.

The post Heart. Soul. Pen. Find Your Voice on the Page With Robin Finn first appeared on The Creative Penn.

4 months ago

11

4 months ago

11

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·