How are publishers using AI and what are the potential use cases in the future? Why is this an exciting time in publishing for those who use the new tools to expand their creative possibilities? Thad McIlroy and I have a wonderful discussion about the current state of AI in publishing, and where we think it might be going next.

In the intro, Audible tests AI-powered search [TechCrunch]; How to avoid book marketing overwhelm [Author Media]; Top 17 self-publishing companies [Nerdy Novelist]; How I professionally self-publish; 30% off ebooks & audio at CreativePennBooks.com, use discount code AUGUST24.

Today's show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital.com to get started.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

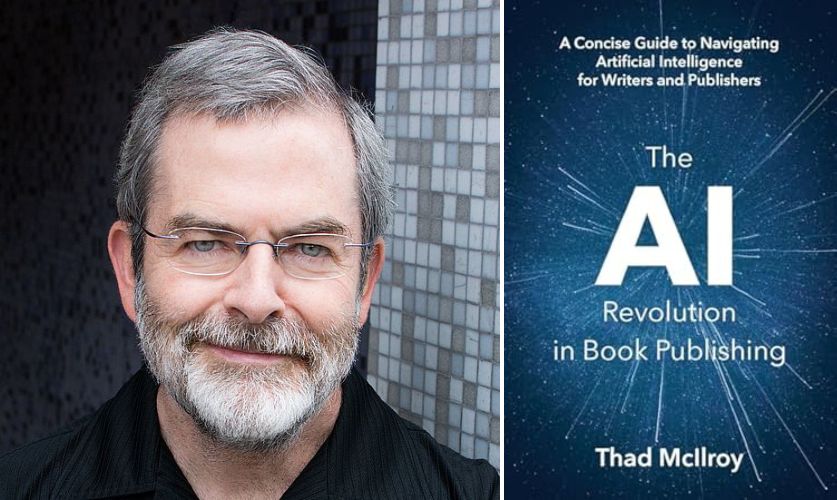

Thad McIlroy is a nonfiction author and contributing editor, writing at the intersection of AI and book publishing, as well as a publishing consultant. His latest book is The AI Revolution in Book Publishing: A Concise Guide to Navigating Artificial Intelligence for Writers and Publishers.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

Why is generative AI so controversial in publishing? Ways in which traditional publishers are using AI tools How platforms are monitoring and placing guidelines on AI work— and why Ingram blocked his book The future of licensing — and synthetic data The increasing importance of high-quality print books Generative AI search and book discoverability Why Thad thinks this is the most exciting time in his 50 year career in publishing

You can find Thad at thefutureofpublishing.com and his new book at Leanpub.com

Transcript of Interview with Thad McIlroy

Joanna: Thad McIlroy is a nonfiction author and contributing editor, writing at the intersection of AI and book publishing, as well as a publishing consultant. His latest book is The AI Revolution in Book Publishing: A Concise Guide to Navigating Artificial Intelligence for Writers and Publishers. So welcome back to the show, Thad.

Thad: Thank you very much, Joanna. It's good to be back. I was thinking, did we start talking first maybe 10 years ago, that we've been staying in touch?

Joanna: Yes, I think so. You've been on the show several times, and I always read your site, The Future of Publishing. It's so good that we're on the same page now, I think, with AI.

Thad: We are, indeed.

Joanna: So let's get into it. I mean, in this industry, we've all been using aspects of AI in publishing for years. Like the Amazon algorithms, for example, or Google search.

Why is the use of generative AI, in particular, so emotional and controversial in the publishing industry, when other businesses are adopting it with enthusiasm?

I know my husband's company is doing it, and there's lots of companies rolling things out, but in publishing, it seems like a no-no.

Thad: It really does, and it's such a fraught topic. It is such an awkward time to be talking to folks about technology when it's just explosive in many ways and suddenly an untouchable.

I think there's more than one aspect to it, right? There's, on the one hand, this feeling of having been violated. There's so much press about AI companies having hoovered up, as is often said, the content. People have this sense —

Authors have this sense, that every book of theirs has already been ingested into an AI system, which is thoroughly inaccurate.

If you're not following the story closely, and you hear stories of hundreds of thousands of books, you don't have any sense as an author of the fact that it was actually a relatively small number of books that got into some of these large language models. Regardless, the sense is that everything got hoovered up.

Then I think there's a secondary sense that I get from some of my author friends where they say, “Well, if my books are already in there, then the AI can recreate books like mine, and that will push me out of business,” that kind of sense.

That's a hard one to explain exactly why that's not likely to be true in any reasonable way. Then I get a sense from people, too, there's a lot of mystique around AI. Giving it a name like artificial intelligence, and all this science fiction, and so on.

So there's that kind of technological apprehension, which again, you can understand that. Then that leads to this sort of sense that these machines are going to try and take over creativity, which again, is a real sense of violation. So all those things are churning around at the same time.

Joanna: It's so interesting, isn't it? Like that last one, ‘will machines take over creativity?' Or people who leave comments on people like me and other people or use AI saying, “Oh, you should write your own books,” when I've got like 15 years of doing this. It's that somehow it's taking something away. Whereas I was working with Claude.ai earlier today —

I feel so much more creative when I work with Claude and Chat.

Is that the sense you get? I guess where I'm going with this is, so much of the criticism is from people who haven't even tried these models in a proper way, like without a terrible prompt.

Thad: Yes. Yes, exactly. I see people, they'll try ChatGPT, usually that one first, sometimes Claude, whatever. Let's say ChatGPT, they try it, they do a couple of prompts, and the first one you do, you're just kind of amazed. “Wow, it sort of talks to me.”

Then you do the second one and the third one and think, well, it's not really answering the way I thought it would. It's not very clever with what it's saying. Then they'll abandon it. I've talked to so many people who've abandoned it so quickly.

Ethan Mollick, that guy who wrote Co-Intelligence, which I consider the best kind of starter guide to AI, all round starter guide, he says —

You need 10 hours. That's his rough rule of the law of how to expose yourself to the technology before you can abandon it.

You know, after 10 hours, you can say, no, to hell with this, it's not for me. By that point, you've exposed yourself, you've worked with it. You know what it can do, and then you can make an informed choice.

Joanna: Yes, I think that's right. To me, the sense of curiosity and play is so important. It's iterative. I've been using the tools now, and I know you have too, for several years now, these generative ones.

I've been using Midjourney. I've just been playing with version 6.1 which is just being released on Midjourney. Obviously, Claude 3.5 Sonnet is the latest there. Just as we speak today, there's some beta things from ChatGPT around a massive output.

So this is moving really fast. I know different indie authors using generative AI for different things already. But in your book, you do outline ways that traditional publishers are looking at using generative AI tools.

In what ways are publishers using these [generative AI] tools?

Thad: In the book, I go at it from two angles. One, I have a short chapter where I quote from the Big Five because a lot of people in publishing look to them—not necessarily for guidance, it's not like they're going to inform us on the smart way to do these things—but what does HarperCollins say? What does Penguin Random House say? So I got a little section on that. Each of them are sort of tentatively feeling their way through it.

Hachette makes a really interesting distinction, where they say that there are two kinds of ways to use AI, operationally or creatively.

We being a creative house, we banished the use of AI for creativity within Hachette, but we'll use it operationally. You think, well, good luck with that differentiation.

So then there's a whole series of use cases, which I think many of your listeners would be familiar with because publishers are using it in some of the same ways that independent authors are using it.

Whether it be editorially for kind of developmental tasks, or in marketing. Of course, there's lots of interesting use cases for marketing. I think both authors and publishers are doing some nifty things there.

A little bit around production, that seems to be sort of easing in so far. I see it on every side. For a while, it was like, well, it doesn't do much here, but it does more stuff there. Now it seems that it touches everything.

Joanna: Yes, you mentioned the difference between operational and creative. To me, things like marketing have to be creative. They might mean the writing of the book, but sometimes I feel like they're saying these things just to not get authors annoyed.

Thad: Exactly. Clearly, that's what it is.

Joanna: Yes, because I guess on audiobooks, you have a little bit on audiobooks in there, and I can't remember which publisher it is that's now using ElevenLabs for some audio.

Thad: I think Simon & Schuster made a little announcement around that, or maybe it was HarperCollins, who knows which one of the Big Five.

Yes, one of them did announce that, and I'm working with ElevenLabs on my audio.

Joanna: Oh, are you for this book?

Thad: Yes.

Joanna: That's interesting because, yes, I started using them. The biggest problem right now with the ElevenLabs file is even though they probably are the best of breed service for AI audio—I mean, there's Google, but they don't have enough voices, whereas ElevenLabs has so many—but Spotify won't accept their files right now, as we record this at the end of July 2024.

Of course, ACX won't either, because they still only take human files. So this is my pick—

My pick is that either Spotify is going to buy ElevenLabs or that they will allow ElevenLabs files by the end of 2024. What do you think about this?

Thad: I'm with you on that. I mean, because ACX has partially backed down, right? They're still sort of publicly pooh-poohing it, but you can do through ACX an automated workflow which they're reluctantly accepting. Some of those files are now apparently in Audible, so Amazon has stepped back.

I think that all of the companies will see that they have no choice but to accept these files. The whole idea that they're not good enough is clearly untrue at this point. They may not be quite as excellent as if you spend $20,000 on a top tier production, but they're very, very good for the average listener.

Joanna: Yes, and actually, ACX officially doesn't do that, but Amazon KDP has a beta program for US indie authors. So US only, where you can opt in and use their AI generation, but it's published through KDP, not through ACX.

Thad: Oh, that's a very important detail.

Joanna: So there's about 40,000, as of the last press release, AI-generated audiobooks from independent authors in the US right now from that program. I'm actually keeping an audiobook ready to kind of try that. I think that's fascinating.

Thad: That's such an interesting detail.

Joanna: I think that has a lot to do with unions, the narrator unions that are associated with ACX. This is what's so interesting.

Let's talk about the licensing deals because I guess the famous one is the New York Times suing OpenAI over training data. Now we're seeing all these licensing deals, including News Corp, which owns The Telegraph. We've seen The Financial Times, The Atlantic.

News Corp obviously owns HarperCollins, which wasn't included in the licensing, but I mean, who knows. Then recently, an academic publisher Taylor & Francis licensed books to Microsoft.

Here in the UK, the ALCS is looking at licensing for authors, and then the Authors Guild in the US.

What do you think about licensing data to the AI companies?

Are people going to just say, “Alright, we're just going to forget the past. Give us some money,” and it'll shake out that way?

Thad: All is forgiven, that'll be the day. It's so complicated, right? There's so many things at play here, and there's not going to be any easy answers. The outcome, I think, is going to play out over years. This is not something we'll be resolving later this year or early next, anything like that.

For the AI companies, it's clearly impossible to pay for everything. There's just too much content out there. Unless it's a penny a piece kind of thing, there's no way they can license the whole of the web and all of the books that are out there. It's just not viable.

So they're coming up with these short-term licenses. The way I keep looking at those is that when they're standing in front of the judge later this year, next year, on the first court cases, they can say, “Oh, no, we respect copyright. We're doing some of these licenses to demonstrate our respect.”

The judge is going to have to rule on it, and then on appeal, and appeal after that, whether or not it's a fair use. The initial original sin, whether that was fair use under the complexity of the law of fair use.

Simplifying the fair use is the notion that is it fair for an engine to ingest copyrighted content, not to reuse it verbatim, but to learn from it the way we learn as human beings reading content? That's the sort of pro argument.

The other argument is no, you're stealing all this copyrighted content. So when the courts determine on that, let's assume that the courts side with the AI companies and say no, you don't have to pay money.

That's great that you're showing your willingness to do some licensing, but no, legally, you're not required to do so. Then the licenses will disappear very, very quickly at that point. I think they're just trying to make nice at this point during the litigation.

Joanna: Yes, you used the word “fair” before. I mean, what is legal or what is accepted as fair? I mean, fair is so difficult a word.

The reality is with this technology, publishing and books are such a tiny, tiny, tiny perspective of generative AI.

In fact, again this week, Google's DeepMind just got silver medal at the Maths Olympiad. I don't know if you saw that, but this is huge for science.

Of course, DeepMind has the AlphaFold which does protein folding. So my husband works for a drug company, so I very much follow drug development, drug discovery, all of that kind of stuff. We've got some incredible challenges in humanity that these tools will be useful for.

Sometimes I just think, look, it doesn't matter. The rest of it doesn't matter. Save the planet, save us all from all these awful diseases, and you can have your data.

That's sometimes how I think about it.

Thad: Me too. When you think of how important these medical advances are, and clearly they are enabled by this technology. I mean, it's unambiguous that they're getting this enormous value from the technology.

Then you come back to publishing and you say, calm down people. You're actually kind of small potatoes in the whole picture here.

Joanna: Yes, exactly. Although, obviously, we respect you, and I respect copyright and all of that kind of thing, and we would like to make money ourselves.

The other thing on the licensing, you mentioned that a lot of these licenses for a couple of years. I like your angle around the court cases and looking good.

The other thing is that there has been some papers coming out on synthetic data. Some of the new Claude models originally—I say originally, you know how fast it goes—but people have said, “Oh, the models are going to run out of data, and if they ingest their own data, it's just a load of sludge.”

That's old news now. They're now finding that synthetic data can be very, very good and can replace human data. So I was like, actually, we've got a very small window to get these licensing deals because—

Synthetic data itself may replace the need to license human data.

Thad: I agree with that. I bet for your listeners that synthetic data is something that's over their heads understandably. You allude to how that works.

You use the AI to create more text or more images that are, in fact, derivative of their existing engine, but appear as if fresh, as if new, and can be ingested without spoiling the pool. I mean, if that's workable, which I still hear some controversy back and forth on that, but it only makes sense that that could be solved as a problem.

So this book I've just done on AI and book publishing, they don't need my book. They don't need it at all. There's no reason in the world for them to license my book.

Joanna: Yes, that is a good point, actually. Last year, and I know you referenced it in the book, which I was very thrilled about, my article on how generative search was going to change things. This is one of the reasons I've kind of stepped back from self-help books and nonfiction that can be done in other ways.

A lot of the questions that I answer in those books, you can now find through the generative AI. So I've moved much more into the kind of writing where you can't get it from one of these tools.

What I liked about your book, even though you say they wouldn't need it, it's still your organization and your take on the industry. Of course, you've got a platform and people respect your opinion. So I think in that way, what you wrote was not something that could have come out of an AI system in that form.

I think it's worth reminding people that it's still worth writing these books — from a personal perspective.

Thad: Oh, yes. Absolutely. The point you're raising around nonfiction, I agree with you. I've been interviewing a bunch of people and not reporting on it as yet because I'm still trying to figure out exactly how this is going to play out.

Certainly, what we're seeing around the possibilities of AI with nonfiction is exceptional, is extraordinary. There it kind of loops over into the whole education space.

The amount of innovation on the education side, it doesn't quite parallel on the health side or on the health and medicine side, but it is closer to that than it is to publishing. We're seeing some really interesting tech there.

What's the difference between a child in high school or you and I trying to find out the same information? So I think the education space is quite analogous to the nonfiction trade publishing space.

I don't hold out a lot of hope for the existing container, as I keep coming back to that term “container” in the book. The way we express our books right now, we have a very particular mental model of the book container, and I think we have to break that down.

It's not to say that we don't still have a role as authors in creating content, but we have to get away from just thinking it's in 12 chapters, 243 pages, that kind of thing. It can't just be that anymore.

Joanna: I like this idea of the container. What was interesting, there was an article in The Verge by the CEO of The Atlantic, I don't know if you read that about why they did the licensing. He actually said,

“Thank goodness, we have a print magazine, and thank goodness, we have an email list.”

That just made me laugh because myself, and many other indie authors now, we're moving into special print editions. So I've just done my third Kickstarter of silver foil and hardback, and all the things that traditional publishers have specialized in, we're now doing in order to change the container.

So, of course, you can still get my book as an eBook, but I also have these more expensive containers that mean I can still make a living. So, I mean, do you see that happening more, is that digital changes, but print just gets higher and higher quality?

Thad: Yes, I see it on two separate directions. Absolutely, print getting higher quality. I've been considering that for years because as the world becomes more atomized and digitized, the affordances of print become more precious and more remarkable.

Paying attention to print as a tangible instance of creative expression makes perfect sense.

I'm delighted to see authors thinking through all of these opportunities and deluxe editions, that kind of thing.

At the same time, to me, the de-containerization of publishing should also be towards video expression, more expression with audio, multiple languages. So it's also de-containerizing within the digital sphere.

Joanna: Yes, and in fact, that's why ElevenLabs is so interesting. In fact, Spotify has a kind of auto translation function that they're using for very, very popular podcasts. So you can hear some of them in multiple languages in the host’s voice. I mean, these things are just incredible, really.

Let's move into search because I think another reason that the licensing is happening with things like, let's say The Financial Times, which I read here in the UK, is that a lot of people are starting to move their searches into ChatGPT.

So I mainly use ChatGPT for search and browsing. Of course, Bing is taking market share in the background from Google. That's my main way I find books now is I will go and have a chat with Chat about a various topic, and then I'll ask for books.

I'll do that, and then I'll go by the specific book, rather than starting on Amazon or starting elsewhere. Then also as we record this, SearchGPT, which is OpenAI's product, is in a limited release. So things are changing.

How do you think this generative AI search is going to change book discoverability?

Because publishers use traditional media and search so much right now.

Thad: They sure do, and I'm concerned. I mean, I'm glad to hear that you're using ChatGPT in that way. I'm not sure—well, let's try a different angle.

As you said, to treat ChatGPT, for example, as a search engine per se, is not what it was designed to be. So it's not designed to be a fact engine, or it was not originally designed to be, let's say.

Now as they mature a little bit, and they look at the existing landscape, and they see that Google search has been most people's conduit into the web and there's no way to take over the world without embracing the reality that people interact with the world wide web via the search metaphor.

People want to be able to ask questions and get answers, which again, I don't think it's the optimal use for a large language model, but it is a use when combined with a certain factual database.

So I feel like there's going to be a bifurcation within the availability of these engines, the features of these engines, some of which will be fact-oriented, and others will be more creative-oriented, or uses of the LLM that are not necessarily fact-related dependent on fact.

ChatGPT, they're productizing it, as you say, as SearchGPT, recognizing that bifurcation, that search is an individualized function that's not everything that we want to do. That didn't answer your question, I realized.

What does this do to book discoverability? I am actually sort of more worried about it for publishers, on behalf of publishers and authors, because of the thing of being able to get the answers they need.

Like you can get a sufficient answer to many of your questions via these SeachGPTs, let's say. If you can get that answer without having to go to the book, without having to be even aware that there's a book on that topic, discoverability is going to be a whole different kind of challenge for authors and publishers.

Joanna: Yes, and it's funny, one example is gardening. So I've never been into gardening, but now I'm like, I'm 49, I've got a garden, and I decided this year, like seriously, I need to do some gardening. What's so awesome is you can take a picture.

I took a picture of my very messy garden and uploaded it to ChatGPT and said, “Okay, this is my garden. This is where I am in the world. Give me some ideas for garden design.”

Then from there, I carried on chatting around, “Okay, what kind of plants could I put up that would have flowers and that my cats wouldn't die of?” and all of this.

The questions I asked, like, “If I go to the garden center, like what's my list of the things I need to buy?” A couple of years ago, I would have bought a book on gardening, or 10 books on gardening. I'm very aware that my behavior is changing.

Actually, just on book discoverability—I don't know if you knew this, I put it in my article—but I've gone back to trying to focus more on Goodreads because I found that when asking ChatGPT, “Find me books with stonemasons in,” for example, that it would use Goodreads reviews, as well as Amazon, Shopify and book blogs.

It was very interesting how much of Goodreads it used. A lot of us had given up on Goodreads, and now I think like, oh, maybe that's actually important. [More in my episode/article on generative AI search and discoverability.]

Thad: Well, I've done a giveaway on Goodreads with my book. Going on to Goodreads, which I hadn't been on in a while because I'd pretty much given up on it, it's a bit of a waste land, in some sense. Like many of my colleagues who were active as I was some years ago on Goodreads, haven't been for years.

I was looking at my old friends on Goodreads and seeing that they haven't done a thing. So that was a bit discouraging, but at the same time, it's really vibrant in other ways. It still is kind of one of a kind. So it has a role to play.

We're raising several things there too because one of the concerns were authors would say, “Well, it knows about my book.”

It knows about your book not because it read your book, but because it read Goodreads and it read what everybody says about your book.

So that's how it got to know. So it didn't actually steal your book, it stole what people said about your book, which wasn't copyrighted. Or technically maybe it was copyrighted, but in reality, anyone could scrape it. So that's another aspect of Goodreads.

The other thing I'm thinking of as you're saying that because you just raised wonderful several issues there, but on the gardening side, you don't see a heck of a lot of books in bookstores on gardening anymore.

One of the things I've been pondering is the cookbooks, right? Because you obviously don't need cookbooks anymore. I mean, ChatGPT and its brethren do wonderful jobs with recipes. You tell what ingredients you've got, and it can give you 22 recipes.

People buy cookbooks because they're beautiful objects and they're a beautiful presentation format.

I think that's something that authors need to ponder still. They buy travel books too. ChatGPT does a great job on travel-related queries, and yet people still buy those books.

So it's a good provocation to authors to say, well, look at what the machine can do, and then think about what you can do far better than the machine. There will always be things that we can do better than the machines.

Joanna: Yes, I totally agree, and that is definitely the way I'm thinking. You're right on the cooking. I do that too. I use it all the time for cooking. It is just so useful.

Okay, just going back to the book. Just to read a quote, you say,

“When publishers look at AI, they see few opportunities. When I talk to authors about AI, the world is their oyster.”

So I love that, and you say the possibilities are near endless. We've talked about some of those, and I am super positive always on the show. I know there are negative sides, I know there are issues, but I choose to be a techno-optimist.

Many authors are scared, and they're scared of, as you mentioned, some of the things at the beginning. They also worry about submitting to agents or publishers or competitions around where is the line when it comes to what do they count as using AI?

For example, ProWritingAid and Grammarly, which so many people use as part of the editing process, they are now powered by ChatGPT and AI models.

So if you're using any editing software, and we recommend that people should, as well as work with human editors, it's like that is completely different to clicking a button and then just publishing what you output. What do you think as to this disclosure? I mean, most agents and publishers don't even have an AI policy on their website.

What should authors be thinking around AI usage if they want to submit to the more traditional industry?

Thad: There's so much confusion. As you saw, you know, Ingram flagged my book for using AI. It was so deliciously ironic that here's this book that's meant to be an examination of the use of AI in writing and publishing, getting flagged by an AI algorithm that Ingram uses.

It therefore detected AI was in the book, in a section of my book that discusses on how authors can use ChatGPT interfaces kind of thing. So that false identification shows that there's a lot of confusion still out there.

So on the one hand, they know that they don't want this, as you're saying, this unfiltered AI-generated text. That seems pretty clear that we don't want that stuff somehow slipping into the ecosphere.

With the ProWritingAid and all of that, you know, how much AI-generated text is there if you run a chapter of your book through ChatGPT and say, “Give me some constructive suggestions on how to improve this chapter.”

You see that list, and then you use your own skills and your own verbiage to make those changes. Well, it is AI-assisted at that point by any sort of definition. Of course, that's something that the algorithms are not going to be able to pick up on. So all of that, it's kind of long windedness on my part.

We did a webinar back in May, looking very specifically at AI detection and how good the AI-detection software is. It's good, but it makes mistakes like everything else.

No machine can reliably detect whether AI was used if someone puts their mind to not being sloppy about it.

So it can't be found, but then it's like, why, publisher, do you want to find this? Again, it's that kind of that inkling of fear where they're, “We don't want whole books with authors lying about their use of it.” Well, that's not what's going to happen, publisher. That's not the way it's going to play out.

You're going to be able to spot those books without a machine.

Just calm down, accept the fact that authors are starting to use these tools very productively and very constructively, and that's a good thing. That's not a bad thing.

Joanna: It just feels like it's going to take some time before everyone calms down, and before everyone realizes that they are using the tools.

For example, book cover design, there's this sort of vocal anti-AI imagery. Now, Adobe Photoshop and all the main tools use AI in their packages.

I don't even know how anyone can do a book cover right now without using some form of AI. In the same way that these editing softwares have AI in. So it's almost like the lines are so blurred.

Thad: They are. I've talked to a designer, I was on a seminar in Denver a few months ago, and this designer is absolutely fastidious, “We don't allow AI, blah, blah, blah.” So you see those kind of camps too, where they will not let AI touch any of this or that, anything. Well, like you're saying, that's going to change really quickly.

Joanna: Yes, or people are going to have to be painting. Well, then even say you do a painting that you want on the front cover of a book, you still have to take a picture of it, and most of the photo editing software has AI in it.

I also think that maybe with the launch of Apple Intelligence that will be on the new iPhones and the iPads, and which, of course, is powered by OpenAI, and will also, I think, be powered by some of these other models, that's going to just put it on people's devices.

So I almost wonder if this is—and I've said this before—this year one, this is like sort of 2007 for eBooks. You remember all that stuff. “Oh, these are awful. No one's ever going to do this,” and the tsunami of crap for self-publishing. It just feels like that time.

Thad: Yes, indeed. Ethan Mollick makes this point that I've seen a couple other people make too, this is the worst AI you'll ever be working with.

So there's moments where for you and I where we're going, “Oh, wow, I can do this, I can do this,” and then you hear someone say, “This is the worst that you're ever going to see.” It's going to get an order of magnitude better, and you try and get your mind around that at this point. Clearly, that's the case. This is 2007 in eBooks.

If you play it out three years from now, five years from now, it's really going to be exceptional.

You also have a point with the Apple AI. Some people are commenting on their approach of trying to make the AI invisible, which in a sense, is what ProWritingAid and Grammarly do. The AI is semi-visible, but it works in the background, as it does with other spell checkers and grammar checkers.

Apple is kind of intimating a future where everything is AI-enabled and nothing is AI-specific.

Joanna: Yes, and the letters “AI” is a bit like the internet. It's almost meaningless as a term because it encompasses so much.

Our life, and our business practices, and our creativity changed so much with the internet, and they're going to change so much over the next 20 years with AI.

I mean, I love it. I'm grinning here. I know you're grinning. We're both excited about this, and I kind of hope that that's what people will come away with.

Let's just keep focusing on what happened to you with Ingram for a minute because this is what people are worried about. They're worried about being banned by this overenthusiastic algorithm, and not everyone is Thad. You were able to get ahold of Ingram, and they're helping you sort it out.

For example, Amazon's algorithm has banned people not actually necessarily over AI use, because you can just tell Amazon that you're using AI now, there's a disclosure thing when you publish, but this kind of thing is what people worry about.

If a ‘normal' author listening has an Ingram issue, is there a process to follow in terms of appeal? Where do you think the lines are?

Thad: Yes, I was lucky in that sense. Although, I would have stood my ground. I wasn't trying to say to them, you should give me an exemption and pay attention to my problem. I was just trying to raise the issue.

I think every reasonable person accepts that these platforms do need to curate the content that they release into the public. We don't want hate, we don't want this, we don't want that, we don't want sexual, whatever kind of content. So we accept that there has to be some kind of filtering. Good, okay.

So then these platforms say they're also filtering around AI, which Ingram claims they're doing at this point in a less subtle way than Amazon is. So books are going to get caught, and again, as you say, sometimes for AI and sometimes for other things.

The way Ingram does it right now, I got the notice on Friday, there's a button saying, “Click here to appeal it,” click, register your appeal with a one little one line box in which you can explain why you're appealing. Then you get an acknowledgment back saying, we'll get back to you within two weeks.

Then I Googled it, and I could see on Reddit and other places, “I got banned by Ingram, and it took two months to get it resolved.” Well, that's ludicrous, and that was the big point I was trying to make to Ingram. It's because you're so powerful, you have a responsibility that comes with that power.

You cannot just banish someone and tell them that the invisible court of appeal may or may not get back to them within two weeks or two months. That's not a workable system.

Joanna: I encourage authors to join organizations like the Alliance of Independent Authors, and there are some other author organizations as well, but certainly ALLi has an ethical author policy around AI.

It's just way more powerful together I think is the thing. An individual author doesn't have so much say.

I wanted to just return to what you said earlier, which was these platforms don't want this unfiltered AI generation, and that these are the worst models we're ever going to get.

I definitely found Claude 3.5 Sonnet, I had a real moment. I've had a couple of these moments, I'm sure you have too, when you're like, oh, my goodness.

It was interesting with Sonnet because I was thinking, do you know what, I already do not consider myself the best writer in the world. It's never been a thing where I've thought, oh, well, I have to be the best writer, because we know that's completely ridiculous.

If an AI system is a better writer than me, how big a deal is that?

Then I decided, actually, that wasn't a big deal because it has far more data than me, a “bigger brain,” in inverted commas, and thus it comes to, well, what is the nature of what we do?

It's about our creativity and about our spark that starts the process. My process is changing, but what I want to create continues.

These bots and agents as they emerge later on this year, next year, they're going to do my creative bidding, as such.

That, to me, is very exciting, but the reality is there are companies now that are looking at generating to market. So for example—

Let's say you type in a search term, and then the AI can generate a book to fit that.

That's what people are scared of. So how are you navigating this? I mean, we talked a bit about nonfiction, but what about fiction and the different forms of creativity people have?

Thad: That is such a great heart of darkness concern. Indeed, when you try to ponder, let's say genre fiction, because it's easy to talk about genre fiction, because in one sense, the essence of genre is repeatability. You're giving people more of what they actually want, in a sense.

They're reading within a genre, so they want books that fit within that. Sometimes it's a looser definition, but it is a constraint. The genre defines a constraint versus so called literary fiction, which supposedly has no constraints.

So it's easier to imagine the machine taking on the challenge of writing within a particular narrow genre, and perhaps succeeding in producing a work that a reader would enjoy as much as they might enjoy something that a human had created within that same genre.

I don't think it's possible today, but it certainly is conceivable for you or I to see that two years from now, whatever, a little bit down the road.

For some reason, I can't get worried about that, the scenario in which all creative writers are supplanted by machines. It doesn't ring true for some reason. As much as I'm enthusiastic, and as much as I think there's so much promise here, I just don't see the human in the loop disappearing.

Even if creative writers rely more and more on these tools, it's still their unique take on the way they use the tools, and what they accept from the tools, and what they ultimately pull together as the whole manuscript.

That's going to be human adjudicated to whatever extent, as far as I can see, as we move forward. I'm not afraid of the machine replacing the author.

Joanna: No, I agree with you from the author perspective.

We are the creative ones. We create. We're never going to stop creating. What is changing is the business model.

If you think about some of the very genre specific publishers who have imprints where they really do have rules that they give to writers, “Follow these rules for this type of book.” You know who they are, we don't need to mention them, but there are those publishers.

I look at them and I think, their dataset, if they fine tune one of these models. I mean, they're already paying authors very little money for these types of books. Those are the types of publishers who I think may well be looking at this now.

The business person in me goes, they would be crazy not to be looking at this. So almost like, no, I agree with you. I'm not scared at all. Humans are going to keep doing human things.

Publishers who are businesses, with big datasets, who return money to shareholders, it's a different story.

Am I being unfair there? They do have big datasets.

Thad: Indeed. I mean, you can see the possibility that some portion of the marketplace is subsumed in that way. When you put it that way, I can certainly see it.

When I think about the issue around—let's switch it over for a second to book translation. There's another one where translators are justifiably very apprehensive about the future of humans in the translation of books.

My book I've had translated using ChatGPT into 31 languages.

No human who was fluent in those languages has looked at those books. I did some quality checking by doing a reverse translation afterwards.

I translated it into French, and then use ChatGPT to translate the French back into English and compared the English, and it was fascinating actually how close it was and how different it was. It was acceptable, it was good enough, for sure.

So, clearly some portion of the people who work in translation, that work is disappearing. Other work, the higher level translation work, one study I just saw a couple of days ago is showing that that work is actually increasing.

The more talented and more skilled translators are getting more work, while the less skilled ones are getting less work.

So not to be a pejorative around genre writing, I know there's a lot of arbitrariness in these kinds of distinctions, but you could see that some portion of the writing profession could be curtailed with these tools.

Joanna: Which is why I focus much more on author brand. I mean, that's what I love about Kickstarter and our Shopify stores now, is that we're not competing on a marketplace like Amazon. We are going to our customers and doing email marketing and all of this kind of thing.

What you write and connecting with people becomes so much more important.

So as we come to a close, I do want to finish on a positive note, because as I said, you and I both techno optimist. So what are you excited about and—

What attitude will serve authors listening as we all try to surf this wave of change?

Thad: I've been working in publishing now over 50 years, which is like saying I'm a million years old, and therefore should be put out to pasture. And yet, this is the most exciting moment I've seen in publishing in those 50 years.

I couldn't be more delighted with what's going on and more optimistic about the future of creativity, of creative expression, of the ability to reach readers, and to delight readers with creative output.

It takes a really open mind. You have to get beyond the container. As you're saying, you as an author, you're redefining your own role. You have to be willing to redefine your role to take advantage of the opportunities that are here, because there are a gazillion opportunities.

Joanna: Yes, exciting times. I hope we'll keep having these conversations.

Thad: One of the things we didn't talk about, of course, is that—

I use the Leanpub platform, which not enough authors are aware of.

Joanna: Oh yes, tell us a bit more about that.

Thad: Leanpub is fascinating. It's mostly technical books that end up on there, which it shouldn't only be those, but it is pretty much so far.

I wrote the book about AI, which is obviously changing so quickly, therefore you think, well, doing a book is ludicrous. With the Leanpub platform, it allows you to continually revise the work, and people who buy from you on that platform, they get updates that are built into the platform.

So if you want to get the ongoing updated version of the book it is on Leanpub. If you want a print version or a Kindle version, of course, it's on Amazon. It's on all the other platforms.

The only updated version, which is the same price as the Kindle version, is available through Leanpub.

Joanna: Those translations you mentioned, are they all on Leanpub as well? Or are they on Amazon?

Thad: Well, that's another big thing that we'll do a separate show on. I called up Michael Tamblyn, the guy runs Kobo, and said, “Michael, I'm not going to upload 31 translations on Kobo. You're going to have to find a way where I can upload once and somehow link these translations,” which is what Leanpub offers.

If you go to the English page for my book on Leanpub, you'll find all 31 translations there. They're linked to sort of the mother page. There's an anglocentric conception there that each of the other languages are adjunct to the English version, which makes sense. It is non obvious, but it does make sense.

So in the short term, to be able to take advantage of this technology and create. I mean, I could have done 50 translations, but I'm not going to upload 50 different files each with a separate ISBN to Amazon. So there's a big transition going on there.

Joanna: That is so interesting. I think the same for audiobooks. You should just be able to change the voice, change the language, change whatever you want on an app. You shouldn't have to just take the one thing. It's the container, like you said. I love that idea.

Thad: Have you used the ElevenLab's reader? The one they released a few weeks ago.

Joanna: The ElevenLabs Reader? No, I haven't yet.

Thad: You can have Judy Garland or Laurence Olivier reading your book. So I put my book into Sir Laurence reading it. It is so hilarious to hear his voice, his wonderful accent reading your book. You think, well, what's the future of audiobooks if you can just read the eBook?

The only thing that's going to prevent that is DRM, but more and more people are going to say, no, you don't have to create a separate audiobook, you work with one of these reading systems that does a 99.9% good enough job just taking your book on the fly.

Joanna: Exciting times. I love that after 50 years in the business, you're still experimenting and trying new things. You know, you're my hero. That's what I want to be like!

Thad: You will be. I know you will be.

Joanna: Well, thanks so much for your time, Thad. That was great.

Thad: Thank you. It was great to be back.

The post Artificial Intelligence (AI) In Publishing With Thad McIlroy first appeared on The Creative Penn.

4 months ago

9

4 months ago

9

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·