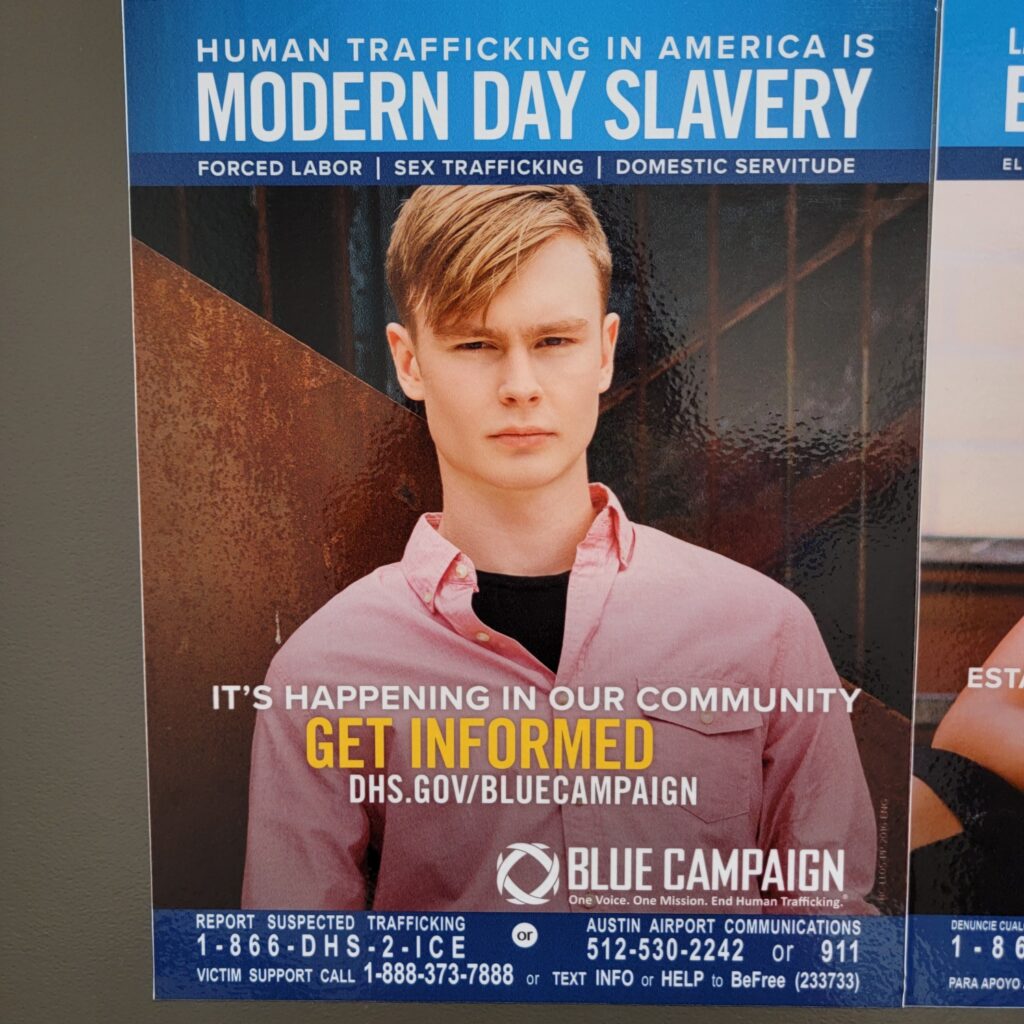

If you've recently been to a U.S. airport, you might have seen posters depicting an attractive, unsmiling young person. These posters are accompanied by sensationalist, hyperbolic claims that young people are at risk of predation from human traffickers. They include a contact number to report suspected trafficking.

The posters are part of the Department of Homeland Security's Blue Campaign, "a national public awareness campaign designed to educate the public, law enforcement, and other industry partners to recognize the indicators of human trafficking, and how to appropriately respond to possible cases."

I noticed one of these posters at the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport in Austin, Texas. I saw it again at Raleigh-Durham. (Note: Though the young man looks an awful lot like my editor, Robby Soave, he swears he is not moonlighting as a sex-trafficking victim impersonator.)

(Lenore Skenazy)

(Lenore Skenazy) I've also recently seen a similar ad featuring a young woman of color. But a few years back, the trafficking posters in airports all looked like Brooks Brothers ads. Today, there's a wider array of ethnicities.

Still, the real question is: By urging travelers to be on high alert for sex-trafficking, are these ads serving any legitimate purpose?

"That guy isn't being trafficked by anyone," says Emily Horowitz, a sociologist and author of From Rage to Reason: Why We Need Sex Crime Laws Based on Facts, Not Fear, when I show her the poster.

Kaytlin Bailey, the founder of Old Pros, a nonprofit that advocates for sex worker rights, and host of The Oldest Profession Podcast, agrees.

"We're not having a problem with white middle-class kids disappearing from soccer games," says Bailey. "That's just not a thing that is happening."

What is happening, she says, is something remarkably akin to the white slavery panic at the turn of the 20th century, with the authorities once again "stoking these middle-class fears that a savage is coming to take your kid."

The sex trafficking of minors is an uncommon occurrence in the United States. When minors do use sex to survive, most "are running away from a worse situation back home, whether they're fleeing impoverished countries or abusive home relationships," says Bailey.

Consider the case of an underage teenager on the run who might agree to sleep with someone in exchange for a place to live. That's certainly a bad situation, and one that policymakers should work to prevent; it is not nearly the same thing as sex traffickers grabbing kids from airport bathrooms, or flying them around the country. Hysteria helps no one: For instance, the oft-cited statistic that the average age of entry into sex work is 13 years old is absolutely false. (Bailey puts it at 26 years old.)

Nonetheless, these posters are multiplying at airports, probably because the people who designed them feel good about fighting a crime that is indeed horrible, even if it is nowhere near as common as these posters seem to imply—and thank goodness for that.

Bailey likes to remind people that most instances of child sexual abuse are committed by someone known to the child, such as a family member or teacher. There are very, very few unfamiliar assailants lurking at airports, shopping malls, and sports stadiums.

"It is literally the opposite of stranger danger," says Bailey.

In the meantime, telling travelers to be on high alert for kidnappers might make life more difficult for interracial families who are just trying to board their plane. In 2019, Cindy McCain, the wife of late Sen. John McCain (R–Ariz.), apologized after she mistakenly reported what she believed to be child trafficking when she saw a child with a woman of a different ethnicity.

Placing posters of young people at airports probably won't do much to stop the underlying causes of human trafficking. They may be ginning up unnecessary fear and panic.

The post Airport Human-Trafficking Posters Are Overstating the Risks to Young People appeared first on Reason.com.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·