I did not set out to write a novel from the point of view of a sociopathic young man, but rather had a manuscript entitled “Gaslit” told from a victim’s perspective. For some reason I could not make “Gaslit” work—I could barely open the document without looking away and giving up. Then it happened. I realized I needed to write from the point of view of the victimizer. I realized there would be a path of destruction and many victims along the way. It was an “aha” moment. It was amazing. The Stalker took shape.

I spent months wholly invested in the interiority of my sociopathic narrator, Doughty—his way of thinking and seeing people, his way of inhabiting the physical world. I often thought of Patricia Highsmith signing her personal correspondence as “Ripley,” the murderous protagonist she wrote into five whole books. Once I had Doughty’s voice, there was glee in how easily his behavior and sense of self came to me. Doughty is an entitled, joyfully abusive young man, who exalts in his ability to hurt others. His relationships are purely transactional, he sees every human as a means to an end—propping up his deluded sense of self and the idea that he is more important, more intelligent, more deserving, an all around superior human than the plebeians who surround him. He is the poster boy for the endless belittlement of women.

Like every woman of my generation, I was taught to keep a key pointed out between two fingers when walking in the dark to fend off rapists. But how to “fight off” what is commonly known as the worst abuse, the emotional abuse women contend with daily? It’s the air we breathe. The ease and flow of being Doughty eventually took its toll on me. So I decided to end the novel sooner than intended. Entitled men are not only running our country, but, on a daily basis, try to assert their power over women. Simply leaving the house forces women to face the Doughtys of the world. Being “strong” or being a “survivor” isn’t some kind of solution. Every single woman I know has to wake up and get through her day being strong, and every single woman I know gets her power and dignity threatened when she steps outside.

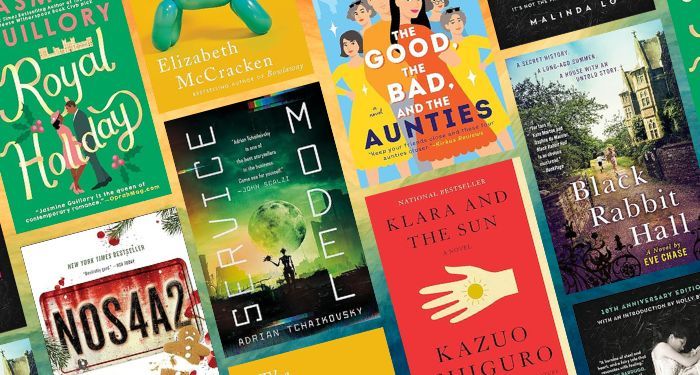

Below are some novels that inspired The Stalker and some new titles that are narrated from the point of view of a psychopath.

The Dwarf by Pär Lagerkvist

The Swedish writer Lagerkvist won the Nobel prize in 1951, and while I love all of his work, The Dwarf is his masterpiece. Piccoline, a court dwarf, keeps a journal that documents, among other acts of violence, the beheading of a princess’s cat. In his deluded worldview, he is always righteous and superior. Everyone but Piccoline is a fool. “What is play?” He muses. “A meaningless dabbling with nothing at all … They all play, all pretend something. Only I despise this pretending. Only I am.” This is a tight, hilarious, and dark look at self-delusion,violence, and the world that upholds it, even nurtures it. Sadly, The Dwarf is timeless in its understanding of society at its most permissive and mankind at its worst.

Ripley’s Game by Patricia Highsmith

I worship Patricia Highsmith’s novels and short stories, her diaries and notebooks. I saw Loving Highsmith, a series of interviews with her lovers, at Film Forum. I can’t get enough of her. Ripley’s Game, focuses on Tom Ripley at a time in his life when he should be content. He is wealthy, married to a woman he adores, and yet when he overhears someone referring to him as having “no taste”, calling him a “philistine” at a party, it sets off his uncanny ability to create a massive storm of terror. The demonization of homosexuality formed Highsmith and informs the character of Ripley. But class is no less salient an issue in the novels by the young woman from Texas who came to New York and garnered great success worldwide. Does a person ever get respect from those in power, if they are not born from it? Will Ripley’s violence ever lead to satisfaction or peace? There are no clear answers, but I love the excruciating pain of reading her novels.

Tampa by Alyssa Nutting

Following Nutting’s excellent story collection, Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls, Tampa enters the mind of Celeste Price, who, like any good predator, has her image all figured out—she’s a middle school teacher married to a police officer! She’s in the perfect situation to fulfill her horrific desires and molest pubescent boys. I love that this book was banned in some bookstores for being too explicit. I love this kind of courage, the courage to offend. I love that Nutting embodies a self aware monster, with stunners like this peppered throughout the novel: “I just wallpapered my cervix with the name of a teenage boy.” I love nothing more than a very finely drawn villain. The ending is perfect in that it is not at all what one hopes for. Is it problematic because most abusers in this world are men? It’s fiction. Let it be. It’s brilliant.

Confessions by Kanae Minato, translated by Stephen Snyder

Speaking of middle schools, this exquisite Japanese thriller is told from multiple points of view, revolving around the tragic death of the daughter of a teacher, Yuko Moriguchi. It begins with her reading a letter she wrote to her class and even though Nabokov hated epistolary components to novels, I don’t. I love them. Filled with plot twists, it is revenge, not unlike in Ripley’s Game, that moves the layered plot forward. The various subplots involve poisoning, bombing, drowning, and a very intense take on motherhood.Uniquely violent and strange, Confessions shows us why translation is so important. The novel explores rage, oppression, revenge and soullessness, all human concerns, but the story unfolds within a unique Japanese environment. My favorite takeaway from the novel is the idea of hikikomori, a condition that afflicts people, usually the young, and causes them to stop leaving their homes. Confessions is deeply fascinating and upsetting, layered in its understanding of human suffering and darkness.

Never Saw Me Coming by Vera Kurian

Set on a college campus in Washington D.C., this novel follows a group of students who are part of a study on psychopaths. Chloe Sevre is attending the fictional John Adams College purely so that she can kill one Will Bachman, who we discover isn’t entirely innocent himself. Then again, is anyone? For Chloe, everything is a cover, and every story is a lie, but her joy in being who she is is real. She’s a total psychopath. At one point she refers to her choice in clothes, facial expressions, and hairstyle as “a whole costume of innocence.” One of the fascinating aspects of this novel is how well it describes the obsessive, premeditated aspect of behavior that often appears as “normal.” How can wearing jeans and no makeup be a smart, well thought out act of premeditation? Kurian, who holds a PhD in social psychology, gets inside the compulsive perfectionism of covering one’s tracks. With twists and surprises, the author undoubtedly uses her knowledge to create a whirlwind of a novel that leads to a very unexpected ending, upending our ideas of when, where, and why evil behaviors occur.

The Looker by Laura Sims

I read The Looker quickly and gleefully, while cringing. And it hurt, too. You feel the pain of the narrator, an unnamed graduate professor of literature, as she spirals into madness. Her husband leaves her after many failed attempts at IVF (which makes him a complete piece of crap in my book). She then becomes obsessed with the famous actress who lives on her Brooklyn block and projects the perfect life onto her. A fantastic examination of the expectations this world puts on women to reproduce and a sympathetic portrait of the pain of a would-be-mother’s lost dream, The Looker also pokes fun at academia, Brooklyn, and privilege. I have a huge soft spot for novels that use all caps and this novel uses them wonderfully. There is a paragraph on hating women, and another on hating men, that alone make the book worth reading. Sims uses humor to temper the darkness of her stalker. The violence in this novel also brings to mind the origins of Thomas Ripley in Highsmith’s first novel about him, The Talented Mr. Ripley. Her acts of violence are not quite premeditated, but they stem from the deep, uncontrollable feelings she suffers as a result of this cold, misogynist world. Brilliant fun.

You Love Me by Caroline Kepnes

Kepnes’s novel mirrors The Stalker and Highsmith’s Ripley series more than any other book on this list in that she writes exclusively from the point of view of a male predator. The third novel in Kepnes’s series, her psychopathic narrator is on the move again (like Ripley!) as Joe moves to the small community of Bainbridge Island, and sets his obsessive stalking behavior on one Mary Kay, a librarian, with a “problematic” (for Joe!) teenage daughter. Kepnes’s bookish sociopath finds everyone in Mary’s life an obstacle to controlling his desired victim and, as he tries to subdue these obstacles, chaos ensues. His voice, his way of seeing the world, his premeditation which, in his mind, is just being alive correctly, is fabulously narrated. His stalking—hey, he just wants to make sure she’s ok!—his delusional sense of self, every insane thought and action serves his outsized belief in himself. Again, some all caps sentences! Notice all my exclamations! Good on you, Kepnes, for defying the rules of how to write a novel. Break the rules, just like Joe Goldberg does, but you know, he has to. It’s what’s needed. He’s just being a great guy. Why is he so misunderstood? He’s just too brilliant for this world, and just loves women so much. Interesting fact: both Kepnes and I had work in Word Riot, an often subversive online and print journal from the early aughts.

The post 7 Novels Narrated by Sociopaths appeared first on Electric Literature.

.jpg.webp?itok=1zl_MpKg)

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·